Steenrod problem

Haggai Tene (Talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Stub}} | {{Stub}} | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

Revision as of 17:56, 31 March 2011

|

This page has not been refereed. The information given here might be incomplete or provisional. |

1 Introduction

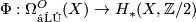

Given a space X, there is a homomorphism  , called the Thom homomorphism, given by

, called the Thom homomorphism, given by ![[M,f] \to f_{*}([M])](/images/math/c/7/1/c711fc19bedc6bd184836dcdf7eb3273.png) where

where ![[M]](/images/math/f/a/0/fa08c3d5d2f54260952acc8a646b5025.png) is the fundamental class of

is the fundamental class of  . The elements in the image of

. The elements in the image of  are called representable.

In certain situations it is convenient to assume that a homology class is representable. In dimensions

are called representable.

In certain situations it is convenient to assume that a homology class is representable. In dimensions  and

and  it is clear that

it is clear that  is surjective (even an isomorphism). It is less obvious in dimension

is surjective (even an isomorphism). It is less obvious in dimension  , but also can be shown geometrically. This made Steenrod raise his famous problem in 1946 [Eilenberg1949]:

, but also can be shown geometrically. This made Steenrod raise his famous problem in 1946 [Eilenberg1949]:

Given a simplicial complex  , is every (integral) homology class representable?

, is every (integral) homology class representable?

The answer was given by Thom in 1954 [Thom1954]. He showed that in dimensions  this is true but in general this is not the case. He constructed a counter example in dimension

this is true but in general this is not the case. He constructed a counter example in dimension  . Thom also showed that the corresponding problem with

. Thom also showed that the corresponding problem with  coefficients is correct, that is the corresponding homomorphism

coefficients is correct, that is the corresponding homomorphism  is surjective.

Thom also proved the following:

is surjective.

Thom also proved the following:

Theorem 1 1.1 (Thom).

For every class in dimension  of integral homology of a finite polyhedron K, there exists a non zero integer

of integral homology of a finite polyhedron K, there exists a non zero integer  , such that the product

, such that the product  is the image of a fundamental class of a closed oriented differentiable manifold.

is the image of a fundamental class of a closed oriented differentiable manifold.

More about that can be found in [Sullivan2004].

2 References

- [Eilenberg1949] S. Eilenberg, On the problems of topology, Ann. of Math. (2) 50 (1949), 247–260. MR0030189 (10,726b) Zbl 0034.25304

- [Sullivan2004] D. Sullivan, René Thom's work on geometric homology and bordism, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) 41 (2004), no.3, 341–350 (electronic). MR2058291 Zbl 1045.57001

- [Thom1954] R. Thom, Quelques propriétés globales des variétés différentiables, Comment. Math. Helv. 28 (1954), 17–86. MR0061823 (15,890a) Zbl 0057.15502

![[M,f] \to f_{*}([M])](/images/math/c/7/1/c711fc19bedc6bd184836dcdf7eb3273.png) where

where ![[M]](/images/math/f/a/0/fa08c3d5d2f54260952acc8a646b5025.png) is the fundamental class of

is the fundamental class of  . The elements in the image of

. The elements in the image of  are called representable.

In certain situations it is convenient to assume that a homology class is representable. In dimensions

are called representable.

In certain situations it is convenient to assume that a homology class is representable. In dimensions  and

and  it is clear that

it is clear that  is surjective (even an isomorphism). It is less obvious in dimension

is surjective (even an isomorphism). It is less obvious in dimension  , but also can be shown geometrically. This made Steenrod raise his famous problem in 1946 [Eilenberg1949]:

, but also can be shown geometrically. This made Steenrod raise his famous problem in 1946 [Eilenberg1949]:

Given a simplicial complex  , is every (integral) homology class representable?

, is every (integral) homology class representable?

The answer was given by Thom in 1954 [Thom1954]. He showed that in dimensions  this is true but in general this is not the case. He constructed a counter example in dimension

this is true but in general this is not the case. He constructed a counter example in dimension  . Thom also showed that the corresponding problem with

. Thom also showed that the corresponding problem with  coefficients is correct, that is the corresponding homomorphism

coefficients is correct, that is the corresponding homomorphism  is surjective.

Thom also proved the following:

is surjective.

Thom also proved the following:

Theorem 1 1.1 (Thom).

For every class in dimension  of integral homology of a finite polyhedron K, there exists a non zero integer

of integral homology of a finite polyhedron K, there exists a non zero integer  , such that the product

, such that the product  is the image of a fundamental class of a closed oriented differentiable manifold.

is the image of a fundamental class of a closed oriented differentiable manifold.

More about that can be found in [Sullivan2004].

2 References

- [Eilenberg1949] S. Eilenberg, On the problems of topology, Ann. of Math. (2) 50 (1949), 247–260. MR0030189 (10,726b) Zbl 0034.25304

- [Sullivan2004] D. Sullivan, René Thom's work on geometric homology and bordism, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) 41 (2004), no.3, 341–350 (electronic). MR2058291 Zbl 1045.57001

- [Thom1954] R. Thom, Quelques propriétés globales des variétés différentiables, Comment. Math. Helv. 28 (1954), 17–86. MR0061823 (15,890a) Zbl 0057.15502

![[M,f] \to f_{*}([M])](/images/math/c/7/1/c711fc19bedc6bd184836dcdf7eb3273.png) where

where ![[M]](/images/math/f/a/0/fa08c3d5d2f54260952acc8a646b5025.png) is the fundamental class of

is the fundamental class of  . The elements in the image of

. The elements in the image of  are called representable.

In certain situations it is convenient to assume that a homology class is representable. In dimensions

are called representable.

In certain situations it is convenient to assume that a homology class is representable. In dimensions  and

and  it is clear that

it is clear that  is surjective (even an isomorphism). It is less obvious in dimension

is surjective (even an isomorphism). It is less obvious in dimension  , but also can be shown geometrically. This made Steenrod raise his famous problem in 1946 [Eilenberg1949]:

, but also can be shown geometrically. This made Steenrod raise his famous problem in 1946 [Eilenberg1949]:

Given a simplicial complex  , is every (integral) homology class representable?

, is every (integral) homology class representable?

The answer was given by Thom in 1954 [Thom1954]. He showed that in dimensions  this is true but in general this is not the case. He constructed a counter example in dimension

this is true but in general this is not the case. He constructed a counter example in dimension  . Thom also showed that the corresponding problem with

. Thom also showed that the corresponding problem with  coefficients is correct, that is the corresponding homomorphism

coefficients is correct, that is the corresponding homomorphism  is surjective.

Thom also proved the following:

is surjective.

Thom also proved the following:

Theorem 1 1.1 (Thom).

For every class in dimension  of integral homology of a finite polyhedron K, there exists a non zero integer

of integral homology of a finite polyhedron K, there exists a non zero integer  , such that the product

, such that the product  is the image of a fundamental class of a closed oriented differentiable manifold.

is the image of a fundamental class of a closed oriented differentiable manifold.

More about that can be found in [Sullivan2004].

2 References

- [Eilenberg1949] S. Eilenberg, On the problems of topology, Ann. of Math. (2) 50 (1949), 247–260. MR0030189 (10,726b) Zbl 0034.25304

- [Sullivan2004] D. Sullivan, René Thom's work on geometric homology and bordism, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) 41 (2004), no.3, 341–350 (electronic). MR2058291 Zbl 1045.57001

- [Thom1954] R. Thom, Quelques propriétés globales des variétés différentiables, Comment. Math. Helv. 28 (1954), 17–86. MR0061823 (15,890a) Zbl 0057.15502

![[M,f] \to f_{*}([M])](/images/math/c/7/1/c711fc19bedc6bd184836dcdf7eb3273.png) where

where ![[M]](/images/math/f/a/0/fa08c3d5d2f54260952acc8a646b5025.png) is the fundamental class of

is the fundamental class of  . The elements in the image of

. The elements in the image of  are called representable.

In certain situations it is convenient to assume that a homology class is representable. In dimensions

are called representable.

In certain situations it is convenient to assume that a homology class is representable. In dimensions  and

and  it is clear that

it is clear that  is surjective (even an isomorphism). It is less obvious in dimension

is surjective (even an isomorphism). It is less obvious in dimension  , but also can be shown geometrically. This made Steenrod raise his famous problem in 1946 [Eilenberg1949]:

, but also can be shown geometrically. This made Steenrod raise his famous problem in 1946 [Eilenberg1949]:

Given a simplicial complex  , is every (integral) homology class representable?

, is every (integral) homology class representable?

The answer was given by Thom in 1954 [Thom1954]. He showed that in dimensions  this is true but in general this is not the case. He constructed a counter example in dimension

this is true but in general this is not the case. He constructed a counter example in dimension  . Thom also showed that the corresponding problem with

. Thom also showed that the corresponding problem with  coefficients is correct, that is the corresponding homomorphism

coefficients is correct, that is the corresponding homomorphism  is surjective.

Thom also proved the following:

is surjective.

Thom also proved the following:

Theorem 1 1.1 (Thom).

For every class in dimension  of integral homology of a finite polyhedron K, there exists a non zero integer

of integral homology of a finite polyhedron K, there exists a non zero integer  , such that the product

, such that the product  is the image of a fundamental class of a closed oriented differentiable manifold.

is the image of a fundamental class of a closed oriented differentiable manifold.

More about that can be found in [Sullivan2004].

2 References

- [Eilenberg1949] S. Eilenberg, On the problems of topology, Ann. of Math. (2) 50 (1949), 247–260. MR0030189 (10,726b) Zbl 0034.25304

- [Sullivan2004] D. Sullivan, René Thom's work on geometric homology and bordism, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) 41 (2004), no.3, 341–350 (electronic). MR2058291 Zbl 1045.57001

- [Thom1954] R. Thom, Quelques propriétés globales des variétés différentiables, Comment. Math. Helv. 28 (1954), 17–86. MR0061823 (15,890a) Zbl 0057.15502