Exotic spheres

|

This page has not been refereed. The information given here might be incomplete or provisional. |

Contents |

1 Introduction

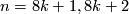

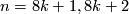

By a homotopy sphere  we mean a closed smooth oriented n-manifold homotopy equivalent to

we mean a closed smooth oriented n-manifold homotopy equivalent to  . The manifold

. The manifold  is called an exotic sphere if it is not diffeomorphic to

is called an exotic sphere if it is not diffeomorphic to  . By the Generalised Poincaré Conjecture proven by Smale, every homotopy sphere in dimension

. By the Generalised Poincaré Conjecture proven by Smale, every homotopy sphere in dimension  is homeomorphic to

is homeomorphic to  : this statement holds in dimension 2 by the classification of surfaces and was famously proven in dimension 4 in [Freedman1982] and in dimension 3 by Perelman. We define

: this statement holds in dimension 2 by the classification of surfaces and was famously proven in dimension 4 in [Freedman1982] and in dimension 3 by Perelman. We define

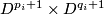

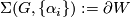

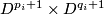

![\displaystyle \Theta_{n} := \{[\Sigma^n] | \Sigma^n \simeq S^n \}](/images/math/0/8/b/08bc0e5cc03477080c3f7936eafb4724.png)

to be the set of oriented diffeomorphism classes of homotopy spheres. Connected sum makes  into an abelian group with inverse given by reversing orientation. An important subgroup of

into an abelian group with inverse given by reversing orientation. An important subgroup of  is

is  which consists of those homotopy spheres which bound parallelisable manifolds.

which consists of those homotopy spheres which bound parallelisable manifolds.

2 Construction and examples

The first exotic spheres discovered were certain 3-sphere bundles over the 4-sphere, [Milnor1956]. Following this discovery there was a rapid development of techniques which construct exotic spheres. We review four such constructions: plumbing, Brieskorn varieties, sphere-bundles and twisting.

2.1 Plumbing

As special case of the following construction goes back at least to [Milnor1959].

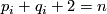

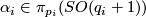

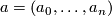

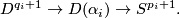

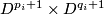

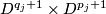

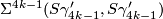

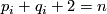

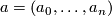

Let  , let

, let  be pairs of positive integers such that

be pairs of positive integers such that  and let

and let  be the clutching functions of

be the clutching functions of  -bundles over

-bundles over

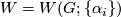

Let  be a graph with vertices

be a graph with vertices  such that the edge set between

such that the edge set between  and

and  , is non-empty only if

, is non-empty only if  . We form the manifold

. We form the manifold  from the disjoint union of the

from the disjoint union of the  by identifying

by identifying  and

and  for each edge in

for each edge in  . If

. If  is simply connected then

is simply connected then

is often a homotopy sphere. We establish some notation for graphs, bundles and define

- let

denote the graph with two vertices and one edge connecting them and define

denote the graph with two vertices and one edge connecting them and define  ,

,

- let

denote the

denote the  -graph,

-graph,

- let

denote the tangent bundle of the

denote the tangent bundle of the  -sphere,

-sphere,

- let

,

,  , denote a generator,

, denote a generator,

- let

, denote a generator:

, denote a generator:

- let

be the suspension homomorphism,

be the suspension homomorphism,

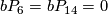

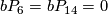

for

for  and

and  for

for  ,

,

- let

be essential.

be essential.

Then we have the following exotic spheres.

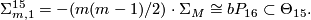

-

, the Milnor sphere, generates

, the Milnor sphere, generates  ,

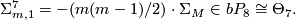

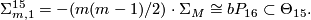

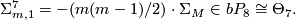

,  .

.

-

, the Kervaire sphere, generates

, the Kervaire sphere, generates  .

.

-

is the inverse of the Milnor sphere for

is the inverse of the Milnor sphere for  .

.

- For general

,

,  is exotic.

is exotic.

- For general

-

, generates

, generates  .

.

-

, generates

, generates  .

.

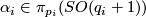

2.2 Brieskorn varieties

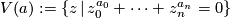

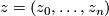

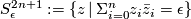

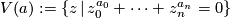

Let  be a point in

be a point in  and let

and let  be a string of n+1 positive integers. Given the complex variety

be a string of n+1 positive integers. Given the complex variety  and the

and the  -sphere

-sphere  for small

for small  , following [Milnor1968]

we define the closed smooth oriented

, following [Milnor1968]

we define the closed smooth oriented  -connected

-connected  -manifold

-manifold

The manifolds  are often called Brieskorn varieties. By construction, every

are often called Brieskorn varieties. By construction, every  lies in

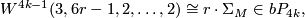

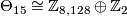

lies in  and so bounds a parallelisable manifold. In [Brieskorn1966] and [Brieskorn1966a] (see also [Hirzebruch&Mayer1968]), it is shown in particular that all homotopy spheres in

and so bounds a parallelisable manifold. In [Brieskorn1966] and [Brieskorn1966a] (see also [Hirzebruch&Mayer1968]), it is shown in particular that all homotopy spheres in  and

and  can be realised as

can be realised as  for some

for some  . Let

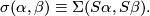

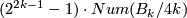

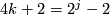

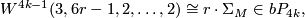

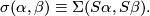

. Let  be a string of 2k-1 2's in a row with

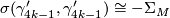

be a string of 2k-1 2's in a row with  , then there are diffeomorphisms

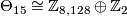

, then there are diffeomorphisms

2.3 Sphere bundles

The first known examples of exotic spheres were discovered by Milnor in [Milnor1956]. They are the total spaces of certain 3-sphere bundles over the 4-sphere as we now explain: the group  parametrises linear

parametrises linear  -sphere bundles over

-sphere bundles over  where a pair

where a pair  gives rise to a bundle with Euler number

gives rise to a bundle with Euler number  and first Pontrjagin class

and first Pontrjagin class  : here we orient

: here we orient  and so identify

and so identify  . If we set

. If we set  then the long exact homotopy sequence of a fibration and Poincare duality ensure that the manifold

then the long exact homotopy sequence of a fibration and Poincare duality ensure that the manifold  , the total space of the bundle

, the total space of the bundle  , is a homotopy sphere. Milnor first used a

, is a homotopy sphere. Milnor first used a  -invariant, called the

-invariant, called the  -invariant, to show, e.g. that

-invariant, to show, e.g. that  is not diffeomorphic to

is not diffeomorphic to  . A little later Kervaire and Milnor [Kervaire&Milnor1963] proved that

. A little later Kervaire and Milnor [Kervaire&Milnor1963] proved that  and Eells and Kuiper [Eells&Kuiper1962] defined a refinement of the

and Eells and Kuiper [Eells&Kuiper1962] defined a refinement of the  -invariant, now called the Eells-Kuiper

-invariant, now called the Eells-Kuiper  -invariant, which in particular gives

-invariant, which in particular gives

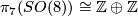

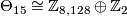

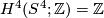

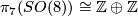

Shimada [Shimada1957] used similar techniques to show that the total spaces of certain 7-sphere bundles over the 8-sphere are exotic 15-spheres. In this case  and the bundle

and the bundle  has Euler number

has Euler number  and second Pontrjagin class

and second Pontrjagin class  . Moreover

. Moreover  where the

where the  -summand is

-summand is  as explained below. Results of [Wall1962a] and [Eells&Kuiper1962] combine to show that

as explained below. Results of [Wall1962a] and [Eells&Kuiper1962] combine to show that

- By Adams' solution of the Hopf-invariant 1 problem, [Adams1958] and [Adams1960], the dimensions n = 3, 7 and 15 are the only dimensions in which a topological n-sphere can be fibre over an m-sphere for 0 < m < n.

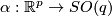

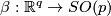

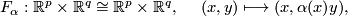

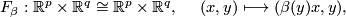

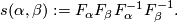

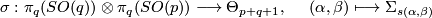

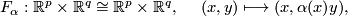

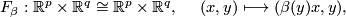

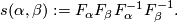

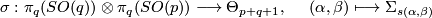

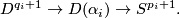

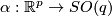

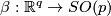

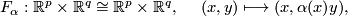

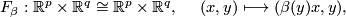

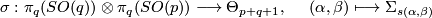

2.4 Twisting

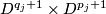

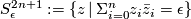

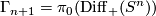

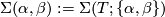

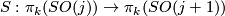

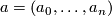

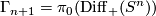

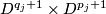

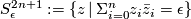

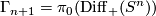

By [Cerf1970] and [Smale1962a] there is an isomorphism  for

for  where

where  is the group of isotopy classes of orientation preserving diffeomorphisms of

is the group of isotopy classes of orientation preserving diffeomorphisms of  . The map is given by

. The map is given by

![\displaystyle \Gamma_{n+1} \to \Theta_{n+1}, ~~~~~[f] \longmapsto \Sigma_{f} := D^{n+1} \cup_f (-D^{n+1}).](/images/math/d/0/7/d072f1885886fceaf69122f3fbd9b643.png)

Hence one may construct exotic (n+1)-spheres by describing diffeomorphisms of  which are not isotopic to the identity. We give such a construction which probably goes back to Milnor: so far the earliest reference found is the problem list of the 1963 Seattle topology conference [Lashof1965].

which are not isotopic to the identity. We give such a construction which probably goes back to Milnor: so far the earliest reference found is the problem list of the 1963 Seattle topology conference [Lashof1965].

Represent  and

and  by smooth compactly supported functions

by smooth compactly supported functions  and

and  and define the following self-diffeomorphisms of

and define the following self-diffeomorphisms of

If follows that  is compactly supported and so extends uniquely to a diffeomorphism of

is compactly supported and so extends uniquely to a diffeomorphism of  . In this way we obtain a bilinear pairing

. In this way we obtain a bilinear pairing

such that

In particular for  we see that

we see that  generates

generates  .

.

3 Invariants

Finding invariants of exotic sphere  which distinguish it from the standard sphere is rather a subtle undertaking. Moreover such invariants are often defined via a manifold

which distinguish it from the standard sphere is rather a subtle undertaking. Moreover such invariants are often defined via a manifold  with

with  . In this case finding an intrinsic definition and or computation of the relevant invariant can also be subtle.

. In this case finding an intrinsic definition and or computation of the relevant invariant can also be subtle.

We begin by listing some invariants which are equal for all exotic spheres.

Proposition 3.1.

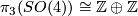

Let  be a closed smooth manifold homeomorphic to the n-sphere. Then

be a closed smooth manifold homeomorphic to the n-sphere. Then

- there is an isomorphism of tangent bundles

,

,

- the signature of

vanishes,

vanishes,

- the Kervaire invariant of

is zero for every framing of

is zero for every framing of  .

.

(To make sense of the first statement remember that the topological space underlying every exotic sphere is homeomorphic to  .)

.)

Remark 3.2.

The analogue of the first statement for the stable tangent bundle was proven in [Kervaire&Milnor1963, Theorem 3.1]. A proof of the unstable statement is given in [Ray&Pedersen1980, Lemma 1.1]. The next two statements are obvious since both the signature and Kervaire invariant are defined to be zero if  and via a symmetric or quadratic form on

and via a symmetric or quadratic form on  if

if  .

.

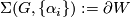

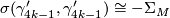

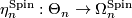

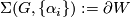

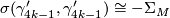

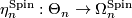

3.1 Bordism classes

As every homotopy sphere is stably parallelisable, homotopy spheres admit  -structures for any

-structures for any  . If

. If  is such that

is such that ![[S^n, F] \mapsto 0 \in \Omega_n^B](/images/math/2/3/1/2314bd522234a19b6171fb659802395f.png) for any stable framing

for any stable framing  of

of  , then we obtain a well-defined homomorphism

, then we obtain a well-defined homomorphism

![\displaystyle \eta^B : \Theta_n \longrightarrow \Omega_n^B, ~~~\Sigma \longmapsto [\Sigma, F].](/images/math/e/2/0/e20d20041da848dffc2059d82978962f.png)

- If

for

for ![[n/2] + 1 < k < n+2](/images/math/b/0/5/b05ba38f77a5f1ca1186c1f95cb25edd.png) then

then  is isomorphic to almost framed bordism and the homomorphism

is isomorphic to almost framed bordism and the homomorphism  is the same thing as the

is the same thing as the  in Theorem 4.1.

in Theorem 4.1.

- Perhaps surprisingly

for all

for all  , as explained in the next subsection.

, as explained in the next subsection.

- In general determining

is a hard an interesting problem.

is a hard an interesting problem.

-

-coboundaries for elements of

-coboundaries for elements of  are often used to define invariants of

are often used to define invariants of  -null bordant homotopy spheres.

-null bordant homotopy spheres.

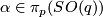

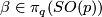

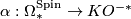

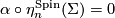

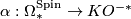

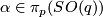

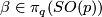

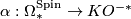

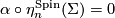

3.2 The α-invariant

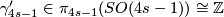

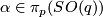

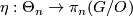

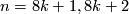

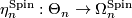

In dimensions  , every exotic sphere

, every exotic sphere  has a unique Spin structure and from above we have the homomorphism

has a unique Spin structure and from above we have the homomorphism  . Recall the

. Recall the  -invariant homomorphism

-invariant homomorphism  and that there are isomorphisms

and that there are isomorphisms  for all

for all  .

.

Theorem 3.3 [Anderson&Brown&Peterson1967].

We have  if and only if

if and only if  and

and  if and only if

if and only if  or

or  .

.

Remark 3.4.

Exotic spheres  with

with  are often called Hitchin spheres, after [Hitchin1974]: see the discussion of curvature below.

are often called Hitchin spheres, after [Hitchin1974]: see the discussion of curvature below.

3.3 The Eels-Kuiper invariant

3.4 The s-invariant

4 Classification

For  and

and  ,

,  . For

. For  ,

,  is unknown. We therefore concentrate on higher dimensions.

is unknown. We therefore concentrate on higher dimensions.

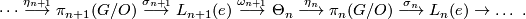

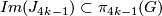

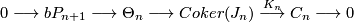

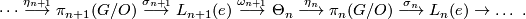

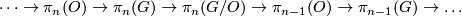

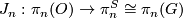

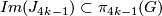

For  , the group of exotic n-spheres

, the group of exotic n-spheres  fits into the following long exact sequence, first discovered in [Kervaire&Milnor1963] (more details can also be found in [Levine1983] and [Lück2001]):

fits into the following long exact sequence, first discovered in [Kervaire&Milnor1963] (more details can also be found in [Levine1983] and [Lück2001]):

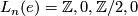

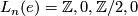

Here  is the n-th L-group of the the trivial group:

is the n-th L-group of the the trivial group:  as n = 0, 1, 2 or 3 modulo 4 and the sequence ends at

as n = 0, 1, 2 or 3 modulo 4 and the sequence ends at  . Also

. Also  is the stable orthogonal group and

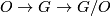

is the stable orthogonal group and  is the stable group of homtopy self-equivalences of the sphere. There is a fibration

is the stable group of homtopy self-equivalences of the sphere. There is a fibration  and the groups

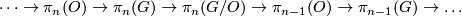

and the groups  fit into the homtopy long exact sequence

fit into the homtopy long exact sequence

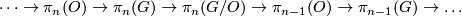

of this fibration. The homomorphism  is the stable J-homomorphism. In particular, by [Serre1951] the groups

is the stable J-homomorphism. In particular, by [Serre1951] the groups  are finite and by [Bott1959], [Adams1966] and [Quillen1971] the domain, image and kernel of

are finite and by [Bott1959], [Adams1966] and [Quillen1971] the domain, image and kernel of  have been completely determined. An important result in [Kervaire&Milnor1963] is that the homomorphism

have been completely determined. An important result in [Kervaire&Milnor1963] is that the homomorphism  is nonzero. The above sequence then gives

is nonzero. The above sequence then gives

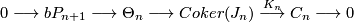

Theorem 4.1 [Kervaire&Milnor1963].

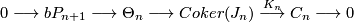

For  , the group

, the group  is finite. Moreover there is an exact sequence

is finite. Moreover there is an exact sequence

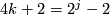

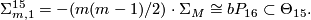

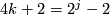

where  , the group of homotopy spheres bounding paralellisable manifolds, is a finite cyclic group which vanishes if

, the group of homotopy spheres bounding paralellisable manifolds, is a finite cyclic group which vanishes if  is even. Moreover

is even. Moreover  unless

unless  when it is

when it is  or

or  .

.

The groups  are known for

are known for  up to approximately 62. In general their determination is a very hard problem. Modulo this problem we see two remaining problems in the determination of

up to approximately 62. In general their determination is a very hard problem. Modulo this problem we see two remaining problems in the determination of  : an extension problem and the comptutation of the order of the groups

: an extension problem and the comptutation of the order of the groups  and

and  . We discuss these in turn.

. We discuss these in turn.

Theorem 4.2 [Brumfiel1968], [Brumfiel1969], [Brumfiel1970].

If  the Kervaire-Milnor extension splits:

the Kervaire-Milnor extension splits:

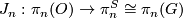

The map  is the Kervaire invariant and by definition

is the Kervaire invariant and by definition  . By the long exact sequence above we have

. By the long exact sequence above we have

Theorem 4.3 [Kervaire&Milnor1963, Section 8].

The group  is either

is either  or

or  . Moreover the following are equivalent:

. Moreover the following are equivalent:

-

,

,

- the Kervaire sphere

is diffeomorphic to the standard sphere,

is diffeomorphic to the standard sphere,

- there is a framed manifold with Kervaire invariant 1:

.

.

Conversely the following are equivalent:

-

,

,

- the Kervaire sphere

is not diffeomorphic to the standard sphere,

is not diffeomorphic to the standard sphere,

- there is no framed manifold with Kervaire invariant 1:

.

.

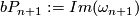

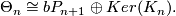

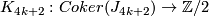

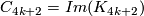

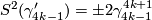

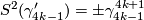

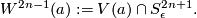

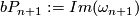

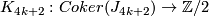

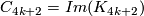

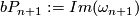

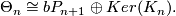

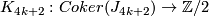

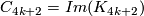

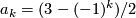

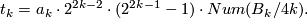

4.1 The orders of bP4k and bP4k+2

The group  is a cyclic group whose order can be determined using the Hirzebruch's signature theorem if one knows the order of

is a cyclic group whose order can be determined using the Hirzebruch's signature theorem if one knows the order of  . Adams determined the latter group up to a factor of two which was settled by Quillen with a positive solution to the Adams conjecture.

. Adams determined the latter group up to a factor of two which was settled by Quillen with a positive solution to the Adams conjecture.

Theorem 4.4.

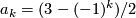

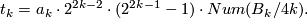

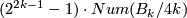

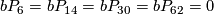

Let  , let

, let  be the k-th Bernoulli number (topologist indexing) and for

be the k-th Bernoulli number (topologist indexing) and for  let

let  denote the numerator of

denote the numerator of  expressed in lowest form. Then for

expressed in lowest form. Then for  , the order of

, the order of  is

is

Remark 4.5.

Note that  is odd so the 2-primary order of

is odd so the 2-primary order of  is

is  while the odd part is

while the odd part is  . Modulo the Adams conjecture the proof appeared in [Kervaire&Milnor1963, Section 7]. Detailed treatments can also be found in [Levine1983, Section 3] and [Lück2001, Chapter 6].

. Modulo the Adams conjecture the proof appeared in [Kervaire&Milnor1963, Section 7]. Detailed treatments can also be found in [Levine1983, Section 3] and [Lück2001, Chapter 6].

The next theorem describes the situation for  which is now almost completely understood as well. References for the theorem are given in the remark which follows it.

which is now almost completely understood as well. References for the theorem are given in the remark which follows it.

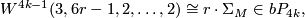

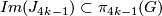

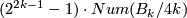

Theorem 4.6.

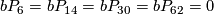

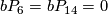

The group  is given as follows:

is given as follows:

-

,

,

-

or

or  ,

,

-

else.

else.

Remark 4.7.

The following is a chronological list of determinations of  :

:

-

, [Kervaire1960a].

, [Kervaire1960a].

-

[Kervaire&Milnor1963].

[Kervaire&Milnor1963].

-

, [Anderson&Brown&Peterson1966a].

, [Anderson&Brown&Peterson1966a].

-

, [Mahowald&Tangora1967].

, [Mahowald&Tangora1967].

-

unless

unless  [Browder1969].

[Browder1969].

-

, [Barratt&Jones&Mahowald1984].

, [Barratt&Jones&Mahowald1984].

-

for

for  , [Hill&Hopkins&Ravenel2009].

, [Hill&Hopkins&Ravenel2009].

5 Further discussion

5.1 Curvature on exotic spheres

For a recent review of which exotic spheres admit metrics of various sorts of positive curvature see [Joachim&Wraith2008].

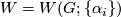

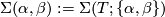

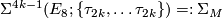

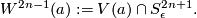

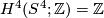

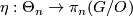

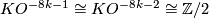

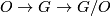

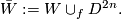

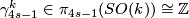

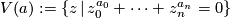

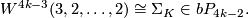

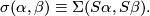

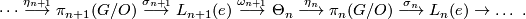

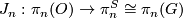

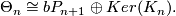

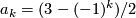

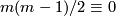

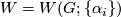

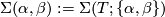

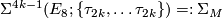

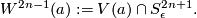

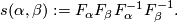

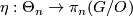

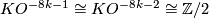

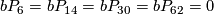

5.2 The Kervaire-Milnor braid

![\displaystyle \def\curv{1.5pc}% Adjust the curvature of the curved arrows here \xymatrix@!R@!C@!0@R=2.5pc@C=4pc{% Adjust the spacing here \pi_n(\Top/O) \ar[dr] \ar@/u\curv/[rr] && \pi_{n-1}(O) \ar[dr] \ar@/u\curv/[rr] && \pi_{n-1}(G) \\ & \pi_n(G/O) \ar[dr] \ar[ur] && \pi_{n-1}(\Top) \ar[dr] \ar[ur] \\ \pi_n(G) \ar[ur] \ar@/d\curv/[rr] && \pi_n(G/\Top) \ar[ur] \ar@/d\curv/[rr] && \pi_{n-1}(\Top/O) }](/images/math/8/3/2/8329c4c4fce71895022bc3e0ed9b9b7b.png)

6 PL manifolds admitting no smooth structure

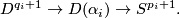

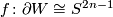

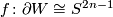

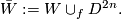

Let  be a plumbing manifold as described above. By a simple version of the Alexander trick, there is a homemorphism

be a plumbing manifold as described above. By a simple version of the Alexander trick, there is a homemorphism  and so we can form the closed topological manifold

and so we can form the closed topological manifold

If  is exotic then it turns out that

is exotic then it turns out that  is a topological manifold which admits no smooth structure!

is a topological manifold which admits no smooth structure!

[Kervaire1960a] shows that  is non-smoothable and the arugments there work for all odd

is non-smoothable and the arugments there work for all odd  so long as the Kervaire sphere is exotic.

so long as the Kervaire sphere is exotic.

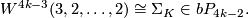

When  is even the proof is more complicated: one first need's Novikov's theorem that the rational Pontrjagin classes of a topological manifold are homeomorphism invariants [Novikov1965b]. Prior to Novikvo's result, some weaker statements were known. For example, when

is even the proof is more complicated: one first need's Novikov's theorem that the rational Pontrjagin classes of a topological manifold are homeomorphism invariants [Novikov1965b]. Prior to Novikvo's result, some weaker statements were known. For example, when  and

and  is the total space of a

is the total space of a  -bundle over

-bundle over  as above and if

as above and if  then by [Tamura1961]

then by [Tamura1961]  is smoothable if and only if

is smoothable if and only if  mod

mod  .[1]; Applying Novikov's theorem we know that

.[1]; Applying Novikov's theorem we know that  is smoothable if and only if

is smoothable if and only if  mod

mod  .

.

7 References

- [Adams1958] J. F. Adams, On the nonexistence of elements of Hopf invariant one, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 64 (1958), 279–282. MR0097059 (20 #3539) Zbl 0178.26106

- [Adams1960] J. F. Adams, On the non-existence of elements of Hopf invariant one, Ann. of Math. (2) 72 (1960), 20–104. MR0141119 (25 #4530) Zbl 0096.17404

- [Adams1966] J. F. Adams, On the groups

. IV, Topology 5 (1966), 21–71. MR0198470 (33 #6628) Zbl 0145.19902

. IV, Topology 5 (1966), 21–71. MR0198470 (33 #6628) Zbl 0145.19902

- [Anderson&Brown&Peterson1966a] D. W. Anderson, E. H. Brown and F. P. Peterson,

-cobordism,

-cobordism,  -characteristic numbers, and the Kervaire invariant, Ann. of Math. (2) 83 (1966), 54–67. MR0189043 (32 #6470) Zbl 0137.42802

-characteristic numbers, and the Kervaire invariant, Ann. of Math. (2) 83 (1966), 54–67. MR0189043 (32 #6470) Zbl 0137.42802

- [Anderson&Brown&Peterson1967] D. W. Anderson, E. H. Brown and F. P. Peterson, The structure of the Spin cobordism ring, Ann. of Math. (2) 86 (1967), 271–298. MR0219077 (36 #2160) Zbl 0156.21605

- [Barratt&Jones&Mahowald1984] M. G. Barratt, J. D. S. Jones and M. E. Mahowald, Relations amongst Toda brackets and the Kervaire invariant in dimension

, J. London Math. Soc. (2) 30 (1984), no.3, 533–550. MR810962 (87g:55025) Zbl 0606.55010

, J. London Math. Soc. (2) 30 (1984), no.3, 533–550. MR810962 (87g:55025) Zbl 0606.55010

- [Bott1959] R. Bott, The stable homotopy of the classical groups, Ann. of Math. (2) 70 (1959), 313–337. MR0110104 (22 #987) Zbl 0129.15601

- [Brieskorn1966] E. Brieskorn, Beispiele zur Differentialtopologie von Singularitäten, Invent. Math. 2 (1966), 1–14. MR0206972 (34 #6788) Zbl 0145.17804

- [Brieskorn1966a] E. V. Brieskorn, Examples of singular normal complex spaces which are topological manifolds, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 55 (1966), 1395–1397. MR0198497 (33 #6652) Zbl 0144.45001

- [Browder1969] W. Browder, The Kervaire invariant of framed manifolds and its generalization, Ann. of Math. (2) 90 (1969), 157–186. MR0251736 (40 #4963) Zbl 0198.28501

- [Brumfiel1968] G. Brumfiel, On the homotopy groups of

and

and  , Ann. of Math. (2) 88 (1968), 291–311. MR0234458 (38 #2775) Zbl 0179.28601

, Ann. of Math. (2) 88 (1968), 291–311. MR0234458 (38 #2775) Zbl 0179.28601

- [Brumfiel1969] G. Brumfiel, On the homotopy groups of

and

and  . II, Topology 8 (1969), 305–311. MR0248830 (40 #2080) Zbl 0179.28601

. II, Topology 8 (1969), 305–311. MR0248830 (40 #2080) Zbl 0179.28601

- [Brumfiel1970] G. Brumfiel, The homotopy groups of

and

and  . III, Michigan Math. J. 17 (1970), 217–224. MR0271938 (42 #6819) Zbl 0201.55901

. III, Michigan Math. J. 17 (1970), 217–224. MR0271938 (42 #6819) Zbl 0201.55901

- [Cerf1970] J. Cerf, La stratification naturelle des espaces de fonctions différentiables réelles et le théorème de la pseudo-isotopie, Inst. Hautes Études Sci. Publ. Math. (1970), no.39, 5–173. MR0292089 (45 #1176) Zbl 0213.25202

- [Eells&Kuiper1962] J. Eells and N. Kuiper, An invariant for certain smooth manifolds, Ann. Mat. Pura Appl. (4) 60 (1962), 93–110. MR0156356 (27 #6280) Zbl 0119.18704

- [Freedman1982] M. H. Freedman, The topology of four-dimensional manifolds, J. Differential Geom. 17 (1982), no.3, 357–453. MR679066 (84b:57006) Zbl 0528.57011

- [Hill&Hopkins&Ravenel2009] M. A. Hill, M. J. Hopkins and D. C. Ravenel, On the non-existence of elements of Kervaire invariant one, (2009). Available at the arXiv:0908.3724.

- [Hirzebruch&Mayer1968] F. Hirzebruch and K. H. Mayer,

-Mannigfaltigkeiten, exotische Sphären und Singularitäten, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1968. MR0229251 (37 #4825) Zbl 0172.25304

-Mannigfaltigkeiten, exotische Sphären und Singularitäten, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1968. MR0229251 (37 #4825) Zbl 0172.25304

- [Hitchin1974] N. Hitchin, Harmonic spinors, Advances in Math. 14 (1974), 1–55. MR0358873 (50 #11332) Zbl 0284.58016

- [Joachim&Wraith2008] M. Joachim and D. J. Wraith, Exotic spheres and curvature, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) 45 (2008), no.4, 595–616. MR2434347 (2009f:57053) Zbl 1149.53020

- [Kervaire&Milnor1963] M. A. Kervaire and J. W. Milnor, Groups of homotopy spheres. I, Ann. of Math. (2) 77 (1963), 504–537. MR0148075 (26 #5584) Zbl 0115.40505

- [Kervaire1960a] M. A. Kervaire, A manifold which does not admit any differentiable structure, Comment. Math. Helv. 34 (1960), 257–270. MR0139172 (25 #2608) Zbl 0145.20304

- [Lashof1965] R. Lashof, Problems in differential and algebraic topology. Seattle Conference, 1963, Ann. of Math. (2) 81 (1965), 565–591. MR0182961 (32 #443) Zbl 0137.17601

- [Levine1983] J. P. Levine, Lectures on groups of homotopy spheres, Algebraic and geometric topology (New Brunswick, N.J., 1983), Lecture Notes in Math., 1126 (1983), 62–95. MR802786 (87i:57031) Zbl 0576.57028

- [Lück2001] W. Lück, A basic introduction to surgery theory, 9 (2001), 1–224. Available from the author's homepage. MR1937016 (2004a:57041) Zbl 1045.57020

- [Mahowald&Tangora1967] M. Mahowald and M. Tangora, Some differentials in the Adams spectral sequence, Topology 6 (1967), 349–369. MR0214072 (35 #4924) Zbl 0213.24901

- [Milnor1956] J. Milnor, On manifolds homeomorphic to the

-sphere, Ann. of Math. (2) 64 (1956), 399–405. MR0082103 (18,498d) Zbl 0072.18402

-sphere, Ann. of Math. (2) 64 (1956), 399–405. MR0082103 (18,498d) Zbl 0072.18402

- [Milnor1959] J. Milnor, Differentiable structures on spheres, Amer. J. Math. 81 (1959), 962–972. MR0110107 (22 #990) Zbl 0111.35501

- [Milnor1968] J. Milnor, Singular points of complex hypersurfaces, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., 1968. MR0239612 (39 #969) Zbl 0224.57014

- [Novikov1965b] S. P. Novikov, The homotopy and topological invariance of certain rational Pontrjagin classes, Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 162 (1965), 1248–1251.

- [Quillen1971] D. Quillen, The Adams conjecture, Topology 10 (1971), 67–80. MR0279804 (43 #5525) Zbl 0219.55013

- [Ray&Pedersen1980] N. Ray and E. K. Pedersen, A fibration for

, 788 (1980), 165–171. MR585659 (82c:57019) Zbl 0436.58012

, 788 (1980), 165–171. MR585659 (82c:57019) Zbl 0436.58012

- [Serre1951] J. Serre, Homologie singulière des espaces fibrès. Applications, Ann. of Math. (2) 54 (1951), 425–505. MR0045386 (13,574g) Zbl 0045.26003

- [Shimada1957] N. Shimada, Differentiable structures on the 15-sphere and Pontrjagin classes of certain manifolds, Nagoya Math. J. 12 (1957), 59–69. MR0096223 (20 #2715) Zbl 0145.20303

- [Smale1962a] S. Smale, On the structure of manifolds, Amer. J. Math. 84 (1962), 387–399. MR0153022 (27 #2991) Zbl 0109.41103

- [Tamura1961] I. Tamura, 8-manifolds admitting no differentiable structure, J. Math. Soc. Japan 13 (1961), 377–382. MR0143220 (26 #780) Zbl 0109.16302

- [Wall1962a] C. T. C. Wall, Classification of

-connected

-connected  -manifolds, Ann. of Math. (2) 75 (1962), 163–189. MR0145540 (26 #3071) Zbl 0218.57022

-manifolds, Ann. of Math. (2) 75 (1962), 163–189. MR0145540 (26 #3071) Zbl 0218.57022

8 Footnotes

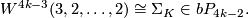

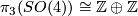

- ↑ Note that Tamura uses a different identification $\pi_3(SO(4)) \cong \Zz \oplus \Zz$ from the one used above.

9 External links

- The Wikipedia page on exotic spheres

- The tabulation of the order of the group of exotic spheres in the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences

- Andrew Ranicki's exotic sphere home page, with many of the original papers: http://www.maths.ed.ac.uk/~aar/exotic.htm

- Including some original correspondence between Kervaire and Milnor

- An animation of exotic 7-spheres. Slides from a presentation by Nile Johsnon at the Second Abel conference in honor of John Milnor.

. The manifold

. The manifold  is called an exotic sphere if it is not diffeomorphic to

is called an exotic sphere if it is not diffeomorphic to  . By the Generalised Poincaré Conjecture proven by Smale, every homotopy sphere in dimension

. By the Generalised Poincaré Conjecture proven by Smale, every homotopy sphere in dimension  is homeomorphic to

is homeomorphic to  : this statement holds in dimension 2 by the classification of surfaces and was famously proven in dimension 4 in [Freedman1982] and in dimension 3 by Perelman. We define

: this statement holds in dimension 2 by the classification of surfaces and was famously proven in dimension 4 in [Freedman1982] and in dimension 3 by Perelman. We define

![\displaystyle \Theta_{n} := \{[\Sigma^n] | \Sigma^n \simeq S^n \}](/images/math/0/8/b/08bc0e5cc03477080c3f7936eafb4724.png)

to be the set of oriented diffeomorphism classes of homotopy spheres. Connected sum makes  into an abelian group with inverse given by reversing orientation. An important subgroup of

into an abelian group with inverse given by reversing orientation. An important subgroup of  is

is  which consists of those homotopy spheres which bound parallelisable manifolds.

which consists of those homotopy spheres which bound parallelisable manifolds.

2 Construction and examples

The first exotic spheres discovered were certain 3-sphere bundles over the 4-sphere, [Milnor1956]. Following this discovery there was a rapid development of techniques which construct exotic spheres. We review four such constructions: plumbing, Brieskorn varieties, sphere-bundles and twisting.

2.1 Plumbing

As special case of the following construction goes back at least to [Milnor1959].

Let  , let

, let  be pairs of positive integers such that

be pairs of positive integers such that  and let

and let  be the clutching functions of

be the clutching functions of  -bundles over

-bundles over

Let  be a graph with vertices

be a graph with vertices  such that the edge set between

such that the edge set between  and

and  , is non-empty only if

, is non-empty only if  . We form the manifold

. We form the manifold  from the disjoint union of the

from the disjoint union of the  by identifying

by identifying  and

and  for each edge in

for each edge in  . If

. If  is simply connected then

is simply connected then

is often a homotopy sphere. We establish some notation for graphs, bundles and define

- let

denote the graph with two vertices and one edge connecting them and define

denote the graph with two vertices and one edge connecting them and define  ,

,

- let

denote the

denote the  -graph,

-graph,

- let

denote the tangent bundle of the

denote the tangent bundle of the  -sphere,

-sphere,

- let

,

,  , denote a generator,

, denote a generator,

- let

, denote a generator:

, denote a generator:

- let

be the suspension homomorphism,

be the suspension homomorphism,

for

for  and

and  for

for  ,

,

- let

be essential.

be essential.

Then we have the following exotic spheres.

-

, the Milnor sphere, generates

, the Milnor sphere, generates  ,

,  .

.

-

, the Kervaire sphere, generates

, the Kervaire sphere, generates  .

.

-

is the inverse of the Milnor sphere for

is the inverse of the Milnor sphere for  .

.

- For general

,

,  is exotic.

is exotic.

- For general

-

, generates

, generates  .

.

-

, generates

, generates  .

.

2.2 Brieskorn varieties

Let  be a point in

be a point in  and let

and let  be a string of n+1 positive integers. Given the complex variety

be a string of n+1 positive integers. Given the complex variety  and the

and the  -sphere

-sphere  for small

for small  , following [Milnor1968]

we define the closed smooth oriented

, following [Milnor1968]

we define the closed smooth oriented  -connected

-connected  -manifold

-manifold

The manifolds  are often called Brieskorn varieties. By construction, every

are often called Brieskorn varieties. By construction, every  lies in

lies in  and so bounds a parallelisable manifold. In [Brieskorn1966] and [Brieskorn1966a] (see also [Hirzebruch&Mayer1968]), it is shown in particular that all homotopy spheres in

and so bounds a parallelisable manifold. In [Brieskorn1966] and [Brieskorn1966a] (see also [Hirzebruch&Mayer1968]), it is shown in particular that all homotopy spheres in  and

and  can be realised as

can be realised as  for some

for some  . Let

. Let  be a string of 2k-1 2's in a row with

be a string of 2k-1 2's in a row with  , then there are diffeomorphisms

, then there are diffeomorphisms

2.3 Sphere bundles

The first known examples of exotic spheres were discovered by Milnor in [Milnor1956]. They are the total spaces of certain 3-sphere bundles over the 4-sphere as we now explain: the group  parametrises linear

parametrises linear  -sphere bundles over

-sphere bundles over  where a pair

where a pair  gives rise to a bundle with Euler number

gives rise to a bundle with Euler number  and first Pontrjagin class

and first Pontrjagin class  : here we orient

: here we orient  and so identify

and so identify  . If we set

. If we set  then the long exact homotopy sequence of a fibration and Poincare duality ensure that the manifold

then the long exact homotopy sequence of a fibration and Poincare duality ensure that the manifold  , the total space of the bundle

, the total space of the bundle  , is a homotopy sphere. Milnor first used a

, is a homotopy sphere. Milnor first used a  -invariant, called the

-invariant, called the  -invariant, to show, e.g. that

-invariant, to show, e.g. that  is not diffeomorphic to

is not diffeomorphic to  . A little later Kervaire and Milnor [Kervaire&Milnor1963] proved that

. A little later Kervaire and Milnor [Kervaire&Milnor1963] proved that  and Eells and Kuiper [Eells&Kuiper1962] defined a refinement of the

and Eells and Kuiper [Eells&Kuiper1962] defined a refinement of the  -invariant, now called the Eells-Kuiper

-invariant, now called the Eells-Kuiper  -invariant, which in particular gives

-invariant, which in particular gives

Shimada [Shimada1957] used similar techniques to show that the total spaces of certain 7-sphere bundles over the 8-sphere are exotic 15-spheres. In this case  and the bundle

and the bundle  has Euler number

has Euler number  and second Pontrjagin class

and second Pontrjagin class  . Moreover

. Moreover  where the

where the  -summand is

-summand is  as explained below. Results of [Wall1962a] and [Eells&Kuiper1962] combine to show that

as explained below. Results of [Wall1962a] and [Eells&Kuiper1962] combine to show that

- By Adams' solution of the Hopf-invariant 1 problem, [Adams1958] and [Adams1960], the dimensions n = 3, 7 and 15 are the only dimensions in which a topological n-sphere can be fibre over an m-sphere for 0 < m < n.

2.4 Twisting

By [Cerf1970] and [Smale1962a] there is an isomorphism  for

for  where

where  is the group of isotopy classes of orientation preserving diffeomorphisms of

is the group of isotopy classes of orientation preserving diffeomorphisms of  . The map is given by

. The map is given by

![\displaystyle \Gamma_{n+1} \to \Theta_{n+1}, ~~~~~[f] \longmapsto \Sigma_{f} := D^{n+1} \cup_f (-D^{n+1}).](/images/math/d/0/7/d072f1885886fceaf69122f3fbd9b643.png)

Hence one may construct exotic (n+1)-spheres by describing diffeomorphisms of  which are not isotopic to the identity. We give such a construction which probably goes back to Milnor: so far the earliest reference found is the problem list of the 1963 Seattle topology conference [Lashof1965].

which are not isotopic to the identity. We give such a construction which probably goes back to Milnor: so far the earliest reference found is the problem list of the 1963 Seattle topology conference [Lashof1965].

Represent  and

and  by smooth compactly supported functions

by smooth compactly supported functions  and

and  and define the following self-diffeomorphisms of

and define the following self-diffeomorphisms of

If follows that  is compactly supported and so extends uniquely to a diffeomorphism of

is compactly supported and so extends uniquely to a diffeomorphism of  . In this way we obtain a bilinear pairing

. In this way we obtain a bilinear pairing

such that

In particular for  we see that

we see that  generates

generates  .

.

3 Invariants

Finding invariants of exotic sphere  which distinguish it from the standard sphere is rather a subtle undertaking. Moreover such invariants are often defined via a manifold

which distinguish it from the standard sphere is rather a subtle undertaking. Moreover such invariants are often defined via a manifold  with

with  . In this case finding an intrinsic definition and or computation of the relevant invariant can also be subtle.

. In this case finding an intrinsic definition and or computation of the relevant invariant can also be subtle.

We begin by listing some invariants which are equal for all exotic spheres.

Proposition 3.1.

Let  be a closed smooth manifold homeomorphic to the n-sphere. Then

be a closed smooth manifold homeomorphic to the n-sphere. Then

- there is an isomorphism of tangent bundles

,

,

- the signature of

vanishes,

vanishes,

- the Kervaire invariant of

is zero for every framing of

is zero for every framing of  .

.

(To make sense of the first statement remember that the topological space underlying every exotic sphere is homeomorphic to  .)

.)

Remark 3.2.

The analogue of the first statement for the stable tangent bundle was proven in [Kervaire&Milnor1963, Theorem 3.1]. A proof of the unstable statement is given in [Ray&Pedersen1980, Lemma 1.1]. The next two statements are obvious since both the signature and Kervaire invariant are defined to be zero if  and via a symmetric or quadratic form on

and via a symmetric or quadratic form on  if

if  .

.

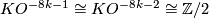

3.1 Bordism classes

As every homotopy sphere is stably parallelisable, homotopy spheres admit  -structures for any

-structures for any  . If

. If  is such that

is such that ![[S^n, F] \mapsto 0 \in \Omega_n^B](/images/math/2/3/1/2314bd522234a19b6171fb659802395f.png) for any stable framing

for any stable framing  of

of  , then we obtain a well-defined homomorphism

, then we obtain a well-defined homomorphism

![\displaystyle \eta^B : \Theta_n \longrightarrow \Omega_n^B, ~~~\Sigma \longmapsto [\Sigma, F].](/images/math/e/2/0/e20d20041da848dffc2059d82978962f.png)

- If

for

for ![[n/2] + 1 < k < n+2](/images/math/b/0/5/b05ba38f77a5f1ca1186c1f95cb25edd.png) then

then  is isomorphic to almost framed bordism and the homomorphism

is isomorphic to almost framed bordism and the homomorphism  is the same thing as the

is the same thing as the  in Theorem 4.1.

in Theorem 4.1.

- Perhaps surprisingly

for all

for all  , as explained in the next subsection.

, as explained in the next subsection.

- In general determining

is a hard an interesting problem.

is a hard an interesting problem.

-

-coboundaries for elements of

-coboundaries for elements of  are often used to define invariants of

are often used to define invariants of  -null bordant homotopy spheres.

-null bordant homotopy spheres.

3.2 The α-invariant

In dimensions  , every exotic sphere

, every exotic sphere  has a unique Spin structure and from above we have the homomorphism

has a unique Spin structure and from above we have the homomorphism  . Recall the

. Recall the  -invariant homomorphism

-invariant homomorphism  and that there are isomorphisms

and that there are isomorphisms  for all

for all  .

.

Theorem 3.3 [Anderson&Brown&Peterson1967].

We have  if and only if

if and only if  and

and  if and only if

if and only if  or

or  .

.

Remark 3.4.

Exotic spheres  with

with  are often called Hitchin spheres, after [Hitchin1974]: see the discussion of curvature below.

are often called Hitchin spheres, after [Hitchin1974]: see the discussion of curvature below.

3.3 The Eels-Kuiper invariant

3.4 The s-invariant

4 Classification

For  and

and  ,

,  . For

. For  ,

,  is unknown. We therefore concentrate on higher dimensions.

is unknown. We therefore concentrate on higher dimensions.

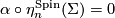

For  , the group of exotic n-spheres

, the group of exotic n-spheres  fits into the following long exact sequence, first discovered in [Kervaire&Milnor1963] (more details can also be found in [Levine1983] and [Lück2001]):

fits into the following long exact sequence, first discovered in [Kervaire&Milnor1963] (more details can also be found in [Levine1983] and [Lück2001]):

Here  is the n-th L-group of the the trivial group:

is the n-th L-group of the the trivial group:  as n = 0, 1, 2 or 3 modulo 4 and the sequence ends at

as n = 0, 1, 2 or 3 modulo 4 and the sequence ends at  . Also

. Also  is the stable orthogonal group and

is the stable orthogonal group and  is the stable group of homtopy self-equivalences of the sphere. There is a fibration

is the stable group of homtopy self-equivalences of the sphere. There is a fibration  and the groups

and the groups  fit into the homtopy long exact sequence

fit into the homtopy long exact sequence

of this fibration. The homomorphism  is the stable J-homomorphism. In particular, by [Serre1951] the groups

is the stable J-homomorphism. In particular, by [Serre1951] the groups  are finite and by [Bott1959], [Adams1966] and [Quillen1971] the domain, image and kernel of

are finite and by [Bott1959], [Adams1966] and [Quillen1971] the domain, image and kernel of  have been completely determined. An important result in [Kervaire&Milnor1963] is that the homomorphism

have been completely determined. An important result in [Kervaire&Milnor1963] is that the homomorphism  is nonzero. The above sequence then gives

is nonzero. The above sequence then gives

Theorem 4.1 [Kervaire&Milnor1963].

For  , the group

, the group  is finite. Moreover there is an exact sequence

is finite. Moreover there is an exact sequence

where  , the group of homotopy spheres bounding paralellisable manifolds, is a finite cyclic group which vanishes if

, the group of homotopy spheres bounding paralellisable manifolds, is a finite cyclic group which vanishes if  is even. Moreover

is even. Moreover  unless

unless  when it is

when it is  or

or  .

.

The groups  are known for

are known for  up to approximately 62. In general their determination is a very hard problem. Modulo this problem we see two remaining problems in the determination of

up to approximately 62. In general their determination is a very hard problem. Modulo this problem we see two remaining problems in the determination of  : an extension problem and the comptutation of the order of the groups

: an extension problem and the comptutation of the order of the groups  and

and  . We discuss these in turn.

. We discuss these in turn.

Theorem 4.2 [Brumfiel1968], [Brumfiel1969], [Brumfiel1970].

If  the Kervaire-Milnor extension splits:

the Kervaire-Milnor extension splits:

The map  is the Kervaire invariant and by definition

is the Kervaire invariant and by definition  . By the long exact sequence above we have

. By the long exact sequence above we have

Theorem 4.3 [Kervaire&Milnor1963, Section 8].

The group  is either

is either  or

or  . Moreover the following are equivalent:

. Moreover the following are equivalent:

-

,

,

- the Kervaire sphere

is diffeomorphic to the standard sphere,

is diffeomorphic to the standard sphere,

- there is a framed manifold with Kervaire invariant 1:

.

.

Conversely the following are equivalent:

-

,

,

- the Kervaire sphere

is not diffeomorphic to the standard sphere,

is not diffeomorphic to the standard sphere,

- there is no framed manifold with Kervaire invariant 1:

.

.

4.1 The orders of bP4k and bP4k+2

The group  is a cyclic group whose order can be determined using the Hirzebruch's signature theorem if one knows the order of

is a cyclic group whose order can be determined using the Hirzebruch's signature theorem if one knows the order of  . Adams determined the latter group up to a factor of two which was settled by Quillen with a positive solution to the Adams conjecture.

. Adams determined the latter group up to a factor of two which was settled by Quillen with a positive solution to the Adams conjecture.

Theorem 4.4.

Let  , let

, let  be the k-th Bernoulli number (topologist indexing) and for

be the k-th Bernoulli number (topologist indexing) and for  let

let  denote the numerator of

denote the numerator of  expressed in lowest form. Then for

expressed in lowest form. Then for  , the order of

, the order of  is

is

Remark 4.5.

Note that  is odd so the 2-primary order of

is odd so the 2-primary order of  is

is  while the odd part is

while the odd part is  . Modulo the Adams conjecture the proof appeared in [Kervaire&Milnor1963, Section 7]. Detailed treatments can also be found in [Levine1983, Section 3] and [Lück2001, Chapter 6].

. Modulo the Adams conjecture the proof appeared in [Kervaire&Milnor1963, Section 7]. Detailed treatments can also be found in [Levine1983, Section 3] and [Lück2001, Chapter 6].

The next theorem describes the situation for  which is now almost completely understood as well. References for the theorem are given in the remark which follows it.

which is now almost completely understood as well. References for the theorem are given in the remark which follows it.

Theorem 4.6.

The group  is given as follows:

is given as follows:

-

,

,

-

or

or  ,

,

-

else.

else.

Remark 4.7.

The following is a chronological list of determinations of  :

:

-

, [Kervaire1960a].

, [Kervaire1960a].

-

[Kervaire&Milnor1963].

[Kervaire&Milnor1963].

-

, [Anderson&Brown&Peterson1966a].

, [Anderson&Brown&Peterson1966a].

-

, [Mahowald&Tangora1967].

, [Mahowald&Tangora1967].

-

unless

unless  [Browder1969].

[Browder1969].

-

, [Barratt&Jones&Mahowald1984].

, [Barratt&Jones&Mahowald1984].

-

for

for  , [Hill&Hopkins&Ravenel2009].

, [Hill&Hopkins&Ravenel2009].

5 Further discussion

5.1 Curvature on exotic spheres

For a recent review of which exotic spheres admit metrics of various sorts of positive curvature see [Joachim&Wraith2008].

5.2 The Kervaire-Milnor braid

![\displaystyle \def\curv{1.5pc}% Adjust the curvature of the curved arrows here \xymatrix@!R@!C@!0@R=2.5pc@C=4pc{% Adjust the spacing here \pi_n(\Top/O) \ar[dr] \ar@/u\curv/[rr] && \pi_{n-1}(O) \ar[dr] \ar@/u\curv/[rr] && \pi_{n-1}(G) \\ & \pi_n(G/O) \ar[dr] \ar[ur] && \pi_{n-1}(\Top) \ar[dr] \ar[ur] \\ \pi_n(G) \ar[ur] \ar@/d\curv/[rr] && \pi_n(G/\Top) \ar[ur] \ar@/d\curv/[rr] && \pi_{n-1}(\Top/O) }](/images/math/8/3/2/8329c4c4fce71895022bc3e0ed9b9b7b.png)

6 PL manifolds admitting no smooth structure

Let  be a plumbing manifold as described above. By a simple version of the Alexander trick, there is a homemorphism

be a plumbing manifold as described above. By a simple version of the Alexander trick, there is a homemorphism  and so we can form the closed topological manifold

and so we can form the closed topological manifold

If  is exotic then it turns out that

is exotic then it turns out that  is a topological manifold which admits no smooth structure!

is a topological manifold which admits no smooth structure!

[Kervaire1960a] shows that  is non-smoothable and the arugments there work for all odd

is non-smoothable and the arugments there work for all odd  so long as the Kervaire sphere is exotic.

so long as the Kervaire sphere is exotic.

When  is even the proof is more complicated: one first need's Novikov's theorem that the rational Pontrjagin classes of a topological manifold are homeomorphism invariants [Novikov1965b]. Prior to Novikvo's result, some weaker statements were known. For example, when

is even the proof is more complicated: one first need's Novikov's theorem that the rational Pontrjagin classes of a topological manifold are homeomorphism invariants [Novikov1965b]. Prior to Novikvo's result, some weaker statements were known. For example, when  and

and  is the total space of a

is the total space of a  -bundle over

-bundle over  as above and if

as above and if  then by [Tamura1961]

then by [Tamura1961]  is smoothable if and only if

is smoothable if and only if  mod

mod  .[1]; Applying Novikov's theorem we know that

.[1]; Applying Novikov's theorem we know that  is smoothable if and only if

is smoothable if and only if  mod

mod  .

.

7 References

- [Adams1958] J. F. Adams, On the nonexistence of elements of Hopf invariant one, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 64 (1958), 279–282. MR0097059 (20 #3539) Zbl 0178.26106

- [Adams1960] J. F. Adams, On the non-existence of elements of Hopf invariant one, Ann. of Math. (2) 72 (1960), 20–104. MR0141119 (25 #4530) Zbl 0096.17404

- [Adams1966] J. F. Adams, On the groups

. IV, Topology 5 (1966), 21–71. MR0198470 (33 #6628) Zbl 0145.19902

. IV, Topology 5 (1966), 21–71. MR0198470 (33 #6628) Zbl 0145.19902

- [Anderson&Brown&Peterson1966a] D. W. Anderson, E. H. Brown and F. P. Peterson,

-cobordism,

-cobordism,  -characteristic numbers, and the Kervaire invariant, Ann. of Math. (2) 83 (1966), 54–67. MR0189043 (32 #6470) Zbl 0137.42802

-characteristic numbers, and the Kervaire invariant, Ann. of Math. (2) 83 (1966), 54–67. MR0189043 (32 #6470) Zbl 0137.42802

- [Anderson&Brown&Peterson1967] D. W. Anderson, E. H. Brown and F. P. Peterson, The structure of the Spin cobordism ring, Ann. of Math. (2) 86 (1967), 271–298. MR0219077 (36 #2160) Zbl 0156.21605

- [Barratt&Jones&Mahowald1984] M. G. Barratt, J. D. S. Jones and M. E. Mahowald, Relations amongst Toda brackets and the Kervaire invariant in dimension

, J. London Math. Soc. (2) 30 (1984), no.3, 533–550. MR810962 (87g:55025) Zbl 0606.55010

, J. London Math. Soc. (2) 30 (1984), no.3, 533–550. MR810962 (87g:55025) Zbl 0606.55010

- [Bott1959] R. Bott, The stable homotopy of the classical groups, Ann. of Math. (2) 70 (1959), 313–337. MR0110104 (22 #987) Zbl 0129.15601

- [Brieskorn1966] E. Brieskorn, Beispiele zur Differentialtopologie von Singularitäten, Invent. Math. 2 (1966), 1–14. MR0206972 (34 #6788) Zbl 0145.17804

- [Brieskorn1966a] E. V. Brieskorn, Examples of singular normal complex spaces which are topological manifolds, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 55 (1966), 1395–1397. MR0198497 (33 #6652) Zbl 0144.45001

- [Browder1969] W. Browder, The Kervaire invariant of framed manifolds and its generalization, Ann. of Math. (2) 90 (1969), 157–186. MR0251736 (40 #4963) Zbl 0198.28501

- [Brumfiel1968] G. Brumfiel, On the homotopy groups of

and

and  , Ann. of Math. (2) 88 (1968), 291–311. MR0234458 (38 #2775) Zbl 0179.28601

, Ann. of Math. (2) 88 (1968), 291–311. MR0234458 (38 #2775) Zbl 0179.28601

- [Brumfiel1969] G. Brumfiel, On the homotopy groups of

and

and  . II, Topology 8 (1969), 305–311. MR0248830 (40 #2080) Zbl 0179.28601

. II, Topology 8 (1969), 305–311. MR0248830 (40 #2080) Zbl 0179.28601

- [Brumfiel1970] G. Brumfiel, The homotopy groups of

and

and  . III, Michigan Math. J. 17 (1970), 217–224. MR0271938 (42 #6819) Zbl 0201.55901

. III, Michigan Math. J. 17 (1970), 217–224. MR0271938 (42 #6819) Zbl 0201.55901

- [Cerf1970] J. Cerf, La stratification naturelle des espaces de fonctions différentiables réelles et le théorème de la pseudo-isotopie, Inst. Hautes Études Sci. Publ. Math. (1970), no.39, 5–173. MR0292089 (45 #1176) Zbl 0213.25202

- [Eells&Kuiper1962] J. Eells and N. Kuiper, An invariant for certain smooth manifolds, Ann. Mat. Pura Appl. (4) 60 (1962), 93–110. MR0156356 (27 #6280) Zbl 0119.18704

- [Freedman1982] M. H. Freedman, The topology of four-dimensional manifolds, J. Differential Geom. 17 (1982), no.3, 357–453. MR679066 (84b:57006) Zbl 0528.57011

- [Hill&Hopkins&Ravenel2009] M. A. Hill, M. J. Hopkins and D. C. Ravenel, On the non-existence of elements of Kervaire invariant one, (2009). Available at the arXiv:0908.3724.

- [Hirzebruch&Mayer1968] F. Hirzebruch and K. H. Mayer,

-Mannigfaltigkeiten, exotische Sphären und Singularitäten, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1968. MR0229251 (37 #4825) Zbl 0172.25304

-Mannigfaltigkeiten, exotische Sphären und Singularitäten, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1968. MR0229251 (37 #4825) Zbl 0172.25304

- [Hitchin1974] N. Hitchin, Harmonic spinors, Advances in Math. 14 (1974), 1–55. MR0358873 (50 #11332) Zbl 0284.58016

- [Joachim&Wraith2008] M. Joachim and D. J. Wraith, Exotic spheres and curvature, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) 45 (2008), no.4, 595–616. MR2434347 (2009f:57053) Zbl 1149.53020

- [Kervaire&Milnor1963] M. A. Kervaire and J. W. Milnor, Groups of homotopy spheres. I, Ann. of Math. (2) 77 (1963), 504–537. MR0148075 (26 #5584) Zbl 0115.40505

- [Kervaire1960a] M. A. Kervaire, A manifold which does not admit any differentiable structure, Comment. Math. Helv. 34 (1960), 257–270. MR0139172 (25 #2608) Zbl 0145.20304

- [Lashof1965] R. Lashof, Problems in differential and algebraic topology. Seattle Conference, 1963, Ann. of Math. (2) 81 (1965), 565–591. MR0182961 (32 #443) Zbl 0137.17601

- [Levine1983] J. P. Levine, Lectures on groups of homotopy spheres, Algebraic and geometric topology (New Brunswick, N.J., 1983), Lecture Notes in Math., 1126 (1983), 62–95. MR802786 (87i:57031) Zbl 0576.57028

- [Lück2001] W. Lück, A basic introduction to surgery theory, 9 (2001), 1–224. Available from the author's homepage. MR1937016 (2004a:57041) Zbl 1045.57020

- [Mahowald&Tangora1967] M. Mahowald and M. Tangora, Some differentials in the Adams spectral sequence, Topology 6 (1967), 349–369. MR0214072 (35 #4924) Zbl 0213.24901

- [Milnor1956] J. Milnor, On manifolds homeomorphic to the

-sphere, Ann. of Math. (2) 64 (1956), 399–405. MR0082103 (18,498d) Zbl 0072.18402

-sphere, Ann. of Math. (2) 64 (1956), 399–405. MR0082103 (18,498d) Zbl 0072.18402

- [Milnor1959] J. Milnor, Differentiable structures on spheres, Amer. J. Math. 81 (1959), 962–972. MR0110107 (22 #990) Zbl 0111.35501

- [Milnor1968] J. Milnor, Singular points of complex hypersurfaces, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., 1968. MR0239612 (39 #969) Zbl 0224.57014

- [Novikov1965b] S. P. Novikov, The homotopy and topological invariance of certain rational Pontrjagin classes, Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 162 (1965), 1248–1251.

- [Quillen1971] D. Quillen, The Adams conjecture, Topology 10 (1971), 67–80. MR0279804 (43 #5525) Zbl 0219.55013

- [Ray&Pedersen1980] N. Ray and E. K. Pedersen, A fibration for

, 788 (1980), 165–171. MR585659 (82c:57019) Zbl 0436.58012

, 788 (1980), 165–171. MR585659 (82c:57019) Zbl 0436.58012

- [Serre1951] J. Serre, Homologie singulière des espaces fibrès. Applications, Ann. of Math. (2) 54 (1951), 425–505. MR0045386 (13,574g) Zbl 0045.26003

- [Shimada1957] N. Shimada, Differentiable structures on the 15-sphere and Pontrjagin classes of certain manifolds, Nagoya Math. J. 12 (1957), 59–69. MR0096223 (20 #2715) Zbl 0145.20303

- [Smale1962a] S. Smale, On the structure of manifolds, Amer. J. Math. 84 (1962), 387–399. MR0153022 (27 #2991) Zbl 0109.41103

- [Tamura1961] I. Tamura, 8-manifolds admitting no differentiable structure, J. Math. Soc. Japan 13 (1961), 377–382. MR0143220 (26 #780) Zbl 0109.16302

- [Wall1962a] C. T. C. Wall, Classification of

-connected

-connected  -manifolds, Ann. of Math. (2) 75 (1962), 163–189. MR0145540 (26 #3071) Zbl 0218.57022

-manifolds, Ann. of Math. (2) 75 (1962), 163–189. MR0145540 (26 #3071) Zbl 0218.57022

8 Footnotes

- ↑ Note that Tamura uses a different identification $\pi_3(SO(4)) \cong \Zz \oplus \Zz$ from the one used above.

9 External links

- The Wikipedia page on exotic spheres

- The tabulation of the order of the group of exotic spheres in the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences

- Andrew Ranicki's exotic sphere home page, with many of the original papers: http://www.maths.ed.ac.uk/~aar/exotic.htm

- Including some original correspondence between Kervaire and Milnor

- An animation of exotic 7-spheres. Slides from a presentation by Nile Johsnon at the Second Abel conference in honor of John Milnor.

. The manifold

. The manifold  is called an exotic sphere if it is not diffeomorphic to

is called an exotic sphere if it is not diffeomorphic to  . By the Generalised Poincaré Conjecture proven by Smale, every homotopy sphere in dimension

. By the Generalised Poincaré Conjecture proven by Smale, every homotopy sphere in dimension  is homeomorphic to

is homeomorphic to  : this statement holds in dimension 2 by the classification of surfaces and was famously proven in dimension 4 in [Freedman1982] and in dimension 3 by Perelman. We define

: this statement holds in dimension 2 by the classification of surfaces and was famously proven in dimension 4 in [Freedman1982] and in dimension 3 by Perelman. We define

![\displaystyle \Theta_{n} := \{[\Sigma^n] | \Sigma^n \simeq S^n \}](/images/math/0/8/b/08bc0e5cc03477080c3f7936eafb4724.png)

to be the set of oriented diffeomorphism classes of homotopy spheres. Connected sum makes  into an abelian group with inverse given by reversing orientation. An important subgroup of

into an abelian group with inverse given by reversing orientation. An important subgroup of  is

is  which consists of those homotopy spheres which bound parallelisable manifolds.

which consists of those homotopy spheres which bound parallelisable manifolds.

2 Construction and examples

The first exotic spheres discovered were certain 3-sphere bundles over the 4-sphere, [Milnor1956]. Following this discovery there was a rapid development of techniques which construct exotic spheres. We review four such constructions: plumbing, Brieskorn varieties, sphere-bundles and twisting.

2.1 Plumbing

As special case of the following construction goes back at least to [Milnor1959].

Let  , let

, let  be pairs of positive integers such that

be pairs of positive integers such that  and let

and let  be the clutching functions of

be the clutching functions of  -bundles over

-bundles over

Let  be a graph with vertices

be a graph with vertices  such that the edge set between

such that the edge set between  and

and  , is non-empty only if

, is non-empty only if  . We form the manifold

. We form the manifold  from the disjoint union of the

from the disjoint union of the  by identifying

by identifying  and

and  for each edge in

for each edge in  . If

. If  is simply connected then

is simply connected then

is often a homotopy sphere. We establish some notation for graphs, bundles and define

- let

denote the graph with two vertices and one edge connecting them and define

denote the graph with two vertices and one edge connecting them and define  ,

,

- let

denote the

denote the  -graph,

-graph,

- let

denote the tangent bundle of the

denote the tangent bundle of the  -sphere,

-sphere,

- let

,

,  , denote a generator,

, denote a generator,

- let

, denote a generator:

, denote a generator:

- let

be the suspension homomorphism,

be the suspension homomorphism,

for

for  and

and  for

for  ,

,

- let

be essential.

be essential.

Then we have the following exotic spheres.

-

, the Milnor sphere, generates

, the Milnor sphere, generates  ,

,  .

.

-

, the Kervaire sphere, generates

, the Kervaire sphere, generates  .

.

-

is the inverse of the Milnor sphere for

is the inverse of the Milnor sphere for  .

.

- For general

,

,  is exotic.

is exotic.

- For general

-

, generates

, generates  .

.

-

, generates

, generates  .

.

2.2 Brieskorn varieties

Let  be a point in

be a point in  and let

and let  be a string of n+1 positive integers. Given the complex variety

be a string of n+1 positive integers. Given the complex variety  and the

and the  -sphere

-sphere  for small

for small  , following [Milnor1968]

we define the closed smooth oriented

, following [Milnor1968]

we define the closed smooth oriented  -connected

-connected  -manifold

-manifold

The manifolds  are often called Brieskorn varieties. By construction, every

are often called Brieskorn varieties. By construction, every  lies in

lies in  and so bounds a parallelisable manifold. In [Brieskorn1966] and [Brieskorn1966a] (see also [Hirzebruch&Mayer1968]), it is shown in particular that all homotopy spheres in

and so bounds a parallelisable manifold. In [Brieskorn1966] and [Brieskorn1966a] (see also [Hirzebruch&Mayer1968]), it is shown in particular that all homotopy spheres in  and

and  can be realised as

can be realised as  for some

for some  . Let

. Let  be a string of 2k-1 2's in a row with

be a string of 2k-1 2's in a row with  , then there are diffeomorphisms

, then there are diffeomorphisms

2.3 Sphere bundles

The first known examples of exotic spheres were discovered by Milnor in [Milnor1956]. They are the total spaces of certain 3-sphere bundles over the 4-sphere as we now explain: the group  parametrises linear

parametrises linear  -sphere bundles over

-sphere bundles over  where a pair

where a pair  gives rise to a bundle with Euler number

gives rise to a bundle with Euler number  and first Pontrjagin class

and first Pontrjagin class  : here we orient

: here we orient  and so identify

and so identify  . If we set

. If we set  then the long exact homotopy sequence of a fibration and Poincare duality ensure that the manifold

then the long exact homotopy sequence of a fibration and Poincare duality ensure that the manifold  , the total space of the bundle

, the total space of the bundle  , is a homotopy sphere. Milnor first used a

, is a homotopy sphere. Milnor first used a  -invariant, called the

-invariant, called the  -invariant, to show, e.g. that

-invariant, to show, e.g. that  is not diffeomorphic to

is not diffeomorphic to  . A little later Kervaire and Milnor [Kervaire&Milnor1963] proved that

. A little later Kervaire and Milnor [Kervaire&Milnor1963] proved that  and Eells and Kuiper [Eells&Kuiper1962] defined a refinement of the

and Eells and Kuiper [Eells&Kuiper1962] defined a refinement of the  -invariant, now called the Eells-Kuiper

-invariant, now called the Eells-Kuiper  -invariant, which in particular gives

-invariant, which in particular gives

Shimada [Shimada1957] used similar techniques to show that the total spaces of certain 7-sphere bundles over the 8-sphere are exotic 15-spheres. In this case  and the bundle

and the bundle  has Euler number

has Euler number  and second Pontrjagin class

and second Pontrjagin class  . Moreover

. Moreover  where the

where the  -summand is

-summand is  as explained below. Results of [Wall1962a] and [Eells&Kuiper1962] combine to show that

as explained below. Results of [Wall1962a] and [Eells&Kuiper1962] combine to show that

- By Adams' solution of the Hopf-invariant 1 problem, [Adams1958] and [Adams1960], the dimensions n = 3, 7 and 15 are the only dimensions in which a topological n-sphere can be fibre over an m-sphere for 0 < m < n.

2.4 Twisting

By [Cerf1970] and [Smale1962a] there is an isomorphism  for

for  where

where  is the group of isotopy classes of orientation preserving diffeomorphisms of

is the group of isotopy classes of orientation preserving diffeomorphisms of  . The map is given by

. The map is given by

![\displaystyle \Gamma_{n+1} \to \Theta_{n+1}, ~~~~~[f] \longmapsto \Sigma_{f} := D^{n+1} \cup_f (-D^{n+1}).](/images/math/d/0/7/d072f1885886fceaf69122f3fbd9b643.png)

Hence one may construct exotic (n+1)-spheres by describing diffeomorphisms of  which are not isotopic to the identity. We give such a construction which probably goes back to Milnor: so far the earliest reference found is the problem list of the 1963 Seattle topology conference [Lashof1965].

which are not isotopic to the identity. We give such a construction which probably goes back to Milnor: so far the earliest reference found is the problem list of the 1963 Seattle topology conference [Lashof1965].

Represent  and

and  by smooth compactly supported functions

by smooth compactly supported functions  and

and  and define the following self-diffeomorphisms of

and define the following self-diffeomorphisms of

If follows that  is compactly supported and so extends uniquely to a diffeomorphism of

is compactly supported and so extends uniquely to a diffeomorphism of  . In this way we obtain a bilinear pairing

. In this way we obtain a bilinear pairing

such that

In particular for  we see that

we see that  generates

generates  .

.

3 Invariants

Finding invariants of exotic sphere  which distinguish it from the standard sphere is rather a subtle undertaking. Moreover such invariants are often defined via a manifold

which distinguish it from the standard sphere is rather a subtle undertaking. Moreover such invariants are often defined via a manifold  with

with  . In this case finding an intrinsic definition and or computation of the relevant invariant can also be subtle.

. In this case finding an intrinsic definition and or computation of the relevant invariant can also be subtle.

We begin by listing some invariants which are equal for all exotic spheres.

Proposition 3.1.

Let  be a closed smooth manifold homeomorphic to the n-sphere. Then

be a closed smooth manifold homeomorphic to the n-sphere. Then

- there is an isomorphism of tangent bundles

,

,

- the signature of

vanishes,

vanishes,

- the Kervaire invariant of

is zero for every framing of

is zero for every framing of  .

.

(To make sense of the first statement remember that the topological space underlying every exotic sphere is homeomorphic to  .)

.)

Remark 3.2.

The analogue of the first statement for the stable tangent bundle was proven in [Kervaire&Milnor1963, Theorem 3.1]. A proof of the unstable statement is given in [Ray&Pedersen1980, Lemma 1.1]. The next two statements are obvious since both the signature and Kervaire invariant are defined to be zero if  and via a symmetric or quadratic form on

and via a symmetric or quadratic form on  if

if  .

.

3.1 Bordism classes

As every homotopy sphere is stably parallelisable, homotopy spheres admit  -structures for any

-structures for any  . If

. If  is such that

is such that ![[S^n, F] \mapsto 0 \in \Omega_n^B](/images/math/2/3/1/2314bd522234a19b6171fb659802395f.png) for any stable framing

for any stable framing  of

of  , then we obtain a well-defined homomorphism

, then we obtain a well-defined homomorphism

![\displaystyle \eta^B : \Theta_n \longrightarrow \Omega_n^B, ~~~\Sigma \longmapsto [\Sigma, F].](/images/math/e/2/0/e20d20041da848dffc2059d82978962f.png)

- If

for

for ![[n/2] + 1 < k < n+2](/images/math/b/0/5/b05ba38f77a5f1ca1186c1f95cb25edd.png) then

then  is isomorphic to almost framed bordism and the homomorphism

is isomorphic to almost framed bordism and the homomorphism  is the same thing as the

is the same thing as the  in Theorem 4.1.

in Theorem 4.1.

- Perhaps surprisingly

for all

for all  , as explained in the next subsection.

, as explained in the next subsection.

- In general determining

is a hard an interesting problem.

is a hard an interesting problem.

-

-coboundaries for elements of

-coboundaries for elements of  are often used to define invariants of

are often used to define invariants of  -null bordant homotopy spheres.

-null bordant homotopy spheres.

3.2 The α-invariant

In dimensions  , every exotic sphere

, every exotic sphere  has a unique Spin structure and from above we have the homomorphism

has a unique Spin structure and from above we have the homomorphism  . Recall the

. Recall the  -invariant homomorphism

-invariant homomorphism  and that there are isomorphisms

and that there are isomorphisms  for all

for all  .

.

Theorem 3.3 [Anderson&Brown&Peterson1967].

We have  if and only if

if and only if  and

and  if and only if

if and only if  or

or  .

.

Remark 3.4.

Exotic spheres  with

with  are often called Hitchin spheres, after [Hitchin1974]: see the discussion of curvature below.

are often called Hitchin spheres, after [Hitchin1974]: see the discussion of curvature below.

3.3 The Eels-Kuiper invariant

3.4 The s-invariant

4 Classification

For  and

and  ,

,  . For

. For  ,

,  is unknown. We therefore concentrate on higher dimensions.

is unknown. We therefore concentrate on higher dimensions.

For  , the group of exotic n-spheres

, the group of exotic n-spheres  fits into the following long exact sequence, first discovered in [Kervaire&Milnor1963] (more details can also be found in [Levine1983] and [Lück2001]):

fits into the following long exact sequence, first discovered in [Kervaire&Milnor1963] (more details can also be found in [Levine1983] and [Lück2001]):

Here  is the n-th L-group of the the trivial group:

is the n-th L-group of the the trivial group:  as n = 0, 1, 2 or 3 modulo 4 and the sequence ends at

as n = 0, 1, 2 or 3 modulo 4 and the sequence ends at  . Also

. Also  is the stable orthogonal group and

is the stable orthogonal group and  is the stable group of homtopy self-equivalences of the sphere. There is a fibration

is the stable group of homtopy self-equivalences of the sphere. There is a fibration  and the groups

and the groups  fit into the homtopy long exact sequence

fit into the homtopy long exact sequence

of this fibration. The homomorphism  is the stable J-homomorphism. In particular, by [Serre1951] the groups

is the stable J-homomorphism. In particular, by [Serre1951] the groups  are finite and by [Bott1959], [Adams1966] and [Quillen1971] the domain, image and kernel of

are finite and by [Bott1959], [Adams1966] and [Quillen1971] the domain, image and kernel of  have been completely determined. An important result in [Kervaire&Milnor1963] is that the homomorphism

have been completely determined. An important result in [Kervaire&Milnor1963] is that the homomorphism  is nonzero. The above sequence then gives

is nonzero. The above sequence then gives

Theorem 4.1 [Kervaire&Milnor1963].

For  , the group

, the group  is finite. Moreover there is an exact sequence

is finite. Moreover there is an exact sequence

where  , the group of homotopy spheres bounding paralellisable manifolds, is a finite cyclic group which vanishes if

, the group of homotopy spheres bounding paralellisable manifolds, is a finite cyclic group which vanishes if  is even. Moreover

is even. Moreover  unless

unless  when it is

when it is  or

or  .

.

The groups  are known for

are known for  up to approximately 62. In general their determination is a very hard problem. Modulo this problem we see two remaining problems in the determination of

up to approximately 62. In general their determination is a very hard problem. Modulo this problem we see two remaining problems in the determination of  : an extension problem and the comptutation of the order of the groups

: an extension problem and the comptutation of the order of the groups  and

and  . We discuss these in turn.

. We discuss these in turn.

Theorem 4.2 [Brumfiel1968], [Brumfiel1969], [Brumfiel1970].

If  the Kervaire-Milnor extension splits:

the Kervaire-Milnor extension splits:

The map  is the Kervaire invariant and by definition

is the Kervaire invariant and by definition  . By the long exact sequence above we have

. By the long exact sequence above we have

Theorem 4.3 [Kervaire&Milnor1963, Section 8].

The group  is either

is either  or

or  . Moreover the following are equivalent:

. Moreover the following are equivalent:

-

,

,

- the Kervaire sphere

is diffeomorphic to the standard sphere,

is diffeomorphic to the standard sphere,

- there is a framed manifold with Kervaire invariant 1:

.

.

Conversely the following are equivalent:

-

,

,

- the Kervaire sphere

is not diffeomorphic to the standard sphere,

is not diffeomorphic to the standard sphere,

- there is no framed manifold with Kervaire invariant 1:

.

.

4.1 The orders of bP4k and bP4k+2

The group  is a cyclic group whose order can be determined using the Hirzebruch's signature theorem if one knows the order of

is a cyclic group whose order can be determined using the Hirzebruch's signature theorem if one knows the order of  . Adams determined the latter group up to a factor of two which was settled by Quillen with a positive solution to the Adams conjecture.

. Adams determined the latter group up to a factor of two which was settled by Quillen with a positive solution to the Adams conjecture.

Theorem 4.4.

Let  , let

, let  be the k-th Bernoulli number (topologist indexing) and for

be the k-th Bernoulli number (topologist indexing) and for  let

let  denote the numerator of

denote the numerator of  expressed in lowest form. Then for

expressed in lowest form. Then for  , the order of

, the order of  is

is

Remark 4.5.

Note that  is odd so the 2-primary order of

is odd so the 2-primary order of  is

is  while the odd part is