Aspherical manifolds

|

An earlier version of this page was published in the Bulletin of the Manifold Atlas: screen, print. You may view the version used for publication as of 12:23, 27 September 2012 and the changes since publication. |

|

The user responsible for this page is Lueck. No other user may edit this page at present. |

|

This page is being refereed under the supervision of the editorial board. Hence the page may not be edited at present. As always, the discussion page remains open for observations and comments. |

1 Introduction

This page is devoted to aspherical closed manifolds.

Definition 1.1.

A space  is called aspherical if it is path connected and all its higher homotopy groups vanish, i.e.,

is called aspherical if it is path connected and all its higher homotopy groups vanish, i.e.,  is trivial for

is trivial for  .

.

Aspherical closed manifolds are very interesting objects since there are many examples, intriguing questions and conjectures about them. For instance:

- Interesting geometric constructions or examples lead to aspherical closed manifolds, e.g., non-positively curved closed manifolds, closed surfaces except

and

and  , irreducible closed orientable

, irreducible closed orientable  -manifolds with infinite fundamental groups, locally symmetric spaces arising from almost connected Lie groups and discrete torsionfree cocompact lattices.

-manifolds with infinite fundamental groups, locally symmetric spaces arising from almost connected Lie groups and discrete torsionfree cocompact lattices.

- There are exotic aspherical closed manifolds which do not come from standard constructions and have unexpected properties, e.g., the universal covering is not homeomorphic to

, they are not triangulable. The key construction method is hyperbolization.

, they are not triangulable. The key construction method is hyperbolization.

- Which groups occur as fundamental groups of aspherical closed manifolds?

- The Borel Conjecture predicts that aspherical closed topological manifolds are topologically rigid, i.e., any homotopy equivalence of aspherical closed manifolds is homotopic to the identity.

- The condition aspherical is of purely homotopy theoretical nature. Nevertheless there are some interesting questions and conjectures such as the Singer Conjecture and the Zero-in-the-Spectrum Conjecture about the spectrum of the Laplace operator on the universal coverings of aspherical closed Riemannian manifolds.

2 Homotopy classification of spaces

From the homotopy theory point of view an aspherical  -complex is completely determined by its fundamental group. Namely,

-complex is completely determined by its fundamental group. Namely,

Theorem 2.1 [Homotopy classification of aspherical spaces].

Two aspherical  -complexes are homotopy equivalent if and only if their fundamental groups are isomorphic.

-complexes are homotopy equivalent if and only if their fundamental groups are isomorphic.

Proof.

By Whitehead's Theorem (see [Whitehead1978, Theorem IV.7.15 on page 182] a map between  -complexes is a homotopy equivalence if and only if it induces on all homotopy groups bijections. Hence it suffices to construct for two aspherical

-complexes is a homotopy equivalence if and only if it induces on all homotopy groups bijections. Hence it suffices to construct for two aspherical  -complexes

-complexes  and

and  together with an isomorphism

together with an isomorphism  a map

a map  which induces

which induces  on the fundamental groups. Any connected

on the fundamental groups. Any connected  -complex is homotopy equivalent to a

-complex is homotopy equivalent to a  -complex with precisely one

-complex with precisely one  -cell, otherwise collapse a maximal sub-tree of the

-cell, otherwise collapse a maximal sub-tree of the  -skeleton to a point. Hence we can assume without loss of generality that the

-skeleton to a point. Hence we can assume without loss of generality that the  -skeleton of

-skeleton of  is a bouquet of

is a bouquet of  -dimensional spheres. The map

-dimensional spheres. The map  tells us how to define

tells us how to define  , where

, where  will denote the

will denote the  -skeleton of

-skeleton of  . The composites of the attaching maps for the two-cells of

. The composites of the attaching maps for the two-cells of  with

with  are null-homotopic by the Seifert-van Kampen Theorem. Hence we can extend

are null-homotopic by the Seifert-van Kampen Theorem. Hence we can extend  to a map

to a map  . Since all higher homotopy groups of

. Since all higher homotopy groups of  are trivial, we can extend

are trivial, we can extend  to a map

to a map  .

.

Lemma 2.2. A  -complex

-complex  is aspherical if and only if it is connected and its universal covering

is aspherical if and only if it is connected and its universal covering  is contractible.

is contractible.

Proof. The projection  induces isomorphisms on the homotopy groups

induces isomorphisms on the homotopy groups  for

for  and a connected

and a connected  -complex is contractible if and only if all its homotopy groups are trivial (see [Whitehead1978, Theorem IV.7.15 on page 182]).

-complex is contractible if and only if all its homotopy groups are trivial (see [Whitehead1978, Theorem IV.7.15 on page 182]).

An aspherical  -complex

-complex  with fundamental group

with fundamental group  is the same as an Eilenberg Mac-Lane space

is the same as an Eilenberg Mac-Lane space  of type

of type  and the same as the classifying space

and the same as the classifying space  for the group

for the group  .

.

3 Examples of aspherical manifolds

3.1 Non-positive curvature

Let  be a closed smooth manifold. Suppose that it possesses a Riemannian metric whose sectional curvature is non-positive, i.e., is

be a closed smooth manifold. Suppose that it possesses a Riemannian metric whose sectional curvature is non-positive, i.e., is  everywhere. Then the universal covering

everywhere. Then the universal covering  inherits a complete Riemannian metric whose sectional curvature is non-positive. Since

inherits a complete Riemannian metric whose sectional curvature is non-positive. Since  is simply-connected and has non-positive sectional curvature, the Hadamard-Cartan Theorem (see [Gallot&Hulin&Lafontaine1987, 3.87 on page 134]) implies that

is simply-connected and has non-positive sectional curvature, the Hadamard-Cartan Theorem (see [Gallot&Hulin&Lafontaine1987, 3.87 on page 134]) implies that  is diffeomorphic to

is diffeomorphic to  and hence contractible. We conclude that

and hence contractible. We conclude that  and hence

and hence  is aspherical.

is aspherical.

3.2 Low-dimensions

A connected closed  -dimensional manifold is homeomorphic to

-dimensional manifold is homeomorphic to  and hence aspherical.

and hence aspherical.

Let  be a connected closed

be a connected closed  -dimensional manifold. Then

-dimensional manifold. Then  is either aspherical or homeomorphic to

is either aspherical or homeomorphic to  or

or  . The following statements are equivalent:

. The following statements are equivalent:

-

is aspherical.

is aspherical.

-

admits a Riemannian metric which is flat, i.e., with sectional curvature constant

admits a Riemannian metric which is flat, i.e., with sectional curvature constant  , or which is hyperbolic, i.e., with sectional curvature constant

, or which is hyperbolic, i.e., with sectional curvature constant  .

.

- The universal covering of

is homeomorphic to

is homeomorphic to  .

.

A connected closed  -manifold

-manifold  is called prime if for any decomposition as a connected sum

is called prime if for any decomposition as a connected sum  one of the summands

one of the summands  or

or  is homeomorphic to

is homeomorphic to  . It is called irreducible if any embedded sphere

. It is called irreducible if any embedded sphere  bounds a disk

bounds a disk  . Every irreducible closed

. Every irreducible closed  -manifold is prime. A prime closed

-manifold is prime. A prime closed  -manifold is either irreducible or an

-manifold is either irreducible or an  -bundle over

-bundle over  (see [Hempel1976, Lemma 3.13 on page 28]). A closed orientable

(see [Hempel1976, Lemma 3.13 on page 28]). A closed orientable  -manifold is aspherical if and only if it is irreducible and has infinite fundamental group. This follows from the Sphere Theorem [Hempel1976, Theorem 4.3 on page 40]. Thurston's Geometrization Conjecture implies that a closed

-manifold is aspherical if and only if it is irreducible and has infinite fundamental group. This follows from the Sphere Theorem [Hempel1976, Theorem 4.3 on page 40]. Thurston's Geometrization Conjecture implies that a closed  -manifold is aspherical if and only if its universal covering is homeomorphic to

-manifold is aspherical if and only if its universal covering is homeomorphic to  . This follows from [Hempel1976, Theorem 13.4 on page 142] and the fact that the

. This follows from [Hempel1976, Theorem 13.4 on page 142] and the fact that the  -dimensional geometries which have compact quotients and whose underlying topological spaces are contractible have as underlying smooth manifold

-dimensional geometries which have compact quotients and whose underlying topological spaces are contractible have as underlying smooth manifold  (see [Scott1983]). A proof of Thurston's Geometrization Conjecture is given in [Morgan&Tian2008] following ideas of Perelman. There are examples of closed orientable

(see [Scott1983]). A proof of Thurston's Geometrization Conjecture is given in [Morgan&Tian2008] following ideas of Perelman. There are examples of closed orientable  -manifolds that are aspherical but do not support a Riemannian metric with non-positive sectional curvature (see [Leeb1995]). For more information about

-manifolds that are aspherical but do not support a Riemannian metric with non-positive sectional curvature (see [Leeb1995]). For more information about  -manifolds we refer for instance to [Hempel1976, Scott1983].

-manifolds we refer for instance to [Hempel1976, Scott1983].

3.3 Torsionfree discrete subgroups of almost connected Lie groups

Let  be a Lie group with finitely many path components. Let

be a Lie group with finitely many path components. Let  be a maximal compact subgroup. Let

be a maximal compact subgroup. Let  be a discrete torsionfree subgroup. Then

be a discrete torsionfree subgroup. Then  is an aspherical closed manifold with fundamental group

is an aspherical closed manifold with fundamental group  since its universal covering

since its universal covering  is diffeomorphic to

is diffeomorphic to  for appropriate

for appropriate  (see [Helgason2001, Theorem 1. in Chapter VI]).

(see [Helgason2001, Theorem 1. in Chapter VI]).

3.4 Products and fibrations

Obviously the product  of two aspherical spaces is again aspherical. More generally, if

of two aspherical spaces is again aspherical. More generally, if  is a fibration for aspherical spaces

is a fibration for aspherical spaces  and

and  , then the long homotopy sequence associated to it shows that

, then the long homotopy sequence associated to it shows that  is aspherical.

is aspherical.

3.5 Pushouts

Let  be a

be a  -complex with sub-

-complex with sub- -complexes

-complexes  ,

,  and

and  such that

such that  and

and  . Suppose that

. Suppose that  ,

,  and

and  are aspherical. Then

are aspherical. Then  is aspherical. The idea of the proof is to check by a Mayer-Vietoris argument that the reduced homology of

is aspherical. The idea of the proof is to check by a Mayer-Vietoris argument that the reduced homology of  is trivial as

is trivial as  is the union of

is the union of  and

and  , and

, and  is the intersection of

is the intersection of  and

and  . Hence

. Hence  is contractible by the Hurewicz Theorem (see [Whitehead1978, Theorem IV.7.15 on page 182]).

is contractible by the Hurewicz Theorem (see [Whitehead1978, Theorem IV.7.15 on page 182]).

3.6 Hyperbolization

A very important construction of aspherical closed manifolds comes from the hyperbolization technique due to Gromov [Gromov1987]. It turns a cell complex into a non-positively curved (and hence aspherical) polyhedron. The rough idea is to define this procedure for simplices such that it is natural under inclusions of simplices and then define the hyperbolization of a simplicial complex by gluing the results for the simplices together as described by the combinatorics of the simplicial complex. The goal is to achieve that the result shares some of the properties of the simplicial complexes one has started with, but additionally to produce a non-positively curved and hence aspherical polyhedron. Since this construction preserves local structures, it turns manifolds into manifolds. We briefly explain what the orientable hyperbolization procedure gives. Further expositions of this construction can be found in [Charney&Davis1995, Davis2002, Davis2008, Davis&Januszkiewicz1991]. We start with a finite-dimensional simplicial complex  and assign to it a cubical cell complex

and assign to it a cubical cell complex  and a natural map

and a natural map  with the following properties:

with the following properties:

-

is non-positively curved and in particular aspherical;

is non-positively curved and in particular aspherical;

- The natural map

induces a surjection on the integral homology;

induces a surjection on the integral homology;

-

is surjective;

is surjective;

- If

is an orientable manifold, then

is an orientable manifold, then

-

is a manifold;

is a manifold;

- The natural map

has degree one;

has degree one;

- There is a stable isomorphism between the tangent bundle

and the pullback

and the pullback  ;

;

3.7 Exotic aspherical closed manifolds

The following result is taken from Davis-Januszkiewicz [Davis&Januszkiewicz1991, Theorem 5a.1].

Theorem 3.1.

There is an aspherical closed  -manifold

-manifold  with the following properties:

with the following properties:

-

is not homotopy equivalent to a

is not homotopy equivalent to a  -manifold;

-manifold;

-

is not triangulable, i.e., not homeomorphic to a simplicial complex;

is not triangulable, i.e., not homeomorphic to a simplicial complex;

- The universal covering

is not homeomorphic to

is not homeomorphic to  ;

;

-

is homotopy equivalent to a piecewise flat, non-positively curved polyhedron.

is homotopy equivalent to a piecewise flat, non-positively curved polyhedron.

The next result is due to Davis-Januszkiewicz [Davis&Januszkiewicz1991, Theorem 5a.4].

Theorem 3.2 [Non-PL-example].

For every  there exists an aspherical closed

there exists an aspherical closed  -manifold which is not homotopy equivalent to a PL-manifold

-manifold which is not homotopy equivalent to a PL-manifold

The proof of the following theorem can be found in [Davis1983], [Davis&Januszkiewicz1991, Theorem 5b.1].

Theorem 3.3 [Exotic universal covering]. For each  there exists an aspherical closed

there exists an aspherical closed  -dimensional manifold such that its universal covering is not homeomorphic to

-dimensional manifold such that its universal covering is not homeomorphic to  .

.

By the Hadamard-Cartan Theorem (see [Gallot&Hulin&Lafontaine1987, 3.87 on page 134]) the manifold appearing in Theorem 3.3 above cannot be homeomorphic to a smooth manifold with Riemannian metric with non-positive sectional curvature. The following theorem is proved in [Davis&Januszkiewicz1991, Theorem 5c.1 and Remark on page 386] by considering the ideal boundary, which is a quasiisometry invariant in the negatively curved case.

Theorem 3.4 [Exotic example with hyperbolic fundamental group].

For every  there exists an aspherical closed smooth

there exists an aspherical closed smooth  -dimensional manifold

-dimensional manifold  which is homeomorphic to a strictly negatively curved polyhedron and has in particular a hyperbolic fundamental group such that the universal covering is homeomorphic to

which is homeomorphic to a strictly negatively curved polyhedron and has in particular a hyperbolic fundamental group such that the universal covering is homeomorphic to  but

but  is not homeomorphic to a smooth manifold with Riemannian metric with negative sectional curvature.

is not homeomorphic to a smooth manifold with Riemannian metric with negative sectional curvature.

The next results are due to Belegradek [Belegradek2006, Corollary 5.1], Mess [Mess1990] and Weinberger (see [Davis2002, Section 13]).

Theorem 3.5 [Exotic fundamental groups].

- For every

there is an aspherical closed manifold of dimension

there is an aspherical closed manifold of dimension  whose fundamental group contains an infinite divisible abelian group;

whose fundamental group contains an infinite divisible abelian group;

- For every

there is an aspherical closed manifold of dimension

there is an aspherical closed manifold of dimension  whose fundamental group has an unsolvable word problem and whose simplicial volume is non-zero.

whose fundamental group has an unsolvable word problem and whose simplicial volume is non-zero.

Notice that a finitely presented group with unsolvable word problem is not a  -group, not hyperbolic, not automatic, not asynchronously automatic, not residually finite and not linear over any commutative ring (see [Belegradek2006, Remark 5.2]). The proof of Theorem 3.5 is based on the reflection group trick as it appears for instance in [Davis2002, Sections 8,10 and 13]. It can be summarized as follows.

-group, not hyperbolic, not automatic, not asynchronously automatic, not residually finite and not linear over any commutative ring (see [Belegradek2006, Remark 5.2]). The proof of Theorem 3.5 is based on the reflection group trick as it appears for instance in [Davis2002, Sections 8,10 and 13]. It can be summarized as follows.

Theorem 3.6 [Reflection group trick].

Let  be a group which possesses a finite model for

be a group which possesses a finite model for  . Then there is an aspherical closed manifold

. Then there is an aspherical closed manifold  and a map

and a map  and

and  such that

such that  .

.

Remark 3.7 [Reflection group trick and various conjectures].

Another interesting immediate consequence of the reflection group trick is (see also [Davis2002, Sections 11]) that many well-known conjectures about groups hold for every group which possesses a finite model for  if and only if it holds for the fundamental group of every aspherical closed manifold. This applies for instance to the Kaplansky Conjecture, Unit Conjecture, Zero-divisor-conjecture, Baum-Connes Conjecture, Farrell-Jones Conjecture for algebraic

if and only if it holds for the fundamental group of every aspherical closed manifold. This applies for instance to the Kaplansky Conjecture, Unit Conjecture, Zero-divisor-conjecture, Baum-Connes Conjecture, Farrell-Jones Conjecture for algebraic  -theory for regular

-theory for regular  , Farrell-Jones Conjecture for algebraic

, Farrell-Jones Conjecture for algebraic  -theory, the vanishing of

-theory, the vanishing of  and of

and of  , For information about these conjectures and their links we refer for instance to [Bartels&Lück&Reich2008],[Lück2002] and [Lück&Reich2005]. Further similar consequences of the reflection group trick can be found in Belegradek [Belegradek2006].

, For information about these conjectures and their links we refer for instance to [Bartels&Lück&Reich2008],[Lück2002] and [Lück&Reich2005]. Further similar consequences of the reflection group trick can be found in Belegradek [Belegradek2006].

4 Non-aspherical closed manifolds

A closed manifold of dimension  with finite fundamental group is never aspherical. So prominent non-aspherical closed manifolds are spheres, lens spaces, real projective spaces and complex projective spaces.

with finite fundamental group is never aspherical. So prominent non-aspherical closed manifolds are spheres, lens spaces, real projective spaces and complex projective spaces.

Lemma 4.1.

The fundamental group of an aspherical finite-dimensional  -complex

-complex  is torsionfree.

is torsionfree.

Proof.

Let  be a finite cyclic subgroup of

be a finite cyclic subgroup of  . We have to show that

. We have to show that  is trivial. Since

is trivial. Since  is aspherical,

is aspherical,  is a finite-dimensional model for

is a finite-dimensional model for  . Hence

. Hence  for large

for large  . This implies that

. This implies that  is trivial.

is trivial.

We mention without proof:

Lemma 4.2.

If  is a connected sum

is a connected sum  of two closed manifolds

of two closed manifolds  and

and  of dimension

of dimension  which are not homotopy equivalent to a sphere, then

which are not homotopy equivalent to a sphere, then  is not aspherical.

is not aspherical.

5 Characteristic classes and bordisms of aspherical closed manifolds

Suppose that  is a closed manifold. Then the pullback of the characteristic classes of

is a closed manifold. Then the pullback of the characteristic classes of  under the natural map

under the natural map  appearing in the Subsection 3.6 about hyperbolization yield the characteristic classes of

appearing in the Subsection 3.6 about hyperbolization yield the characteristic classes of  , and

, and  and

and  have the same characteristic numbers. This shows that the condition aspherical does not impose any restrictions on the characteristic numbers of a manifold. Consider a bordism theory

have the same characteristic numbers. This shows that the condition aspherical does not impose any restrictions on the characteristic numbers of a manifold. Consider a bordism theory  for PL-manifolds or smooth manifolds which is given by imposing conditions on the stable tangent bundle. Examples are unoriented bordism, oriented bordism, framed bordism. Then any bordism class can be represented by an aspherical closed manifold. If two aspherical closed manifolds represent the same bordism class, then one can find an aspherical bordism between them. See [Davis2002, Remarks 15.1] and [Davis&Januszkiewicz1991, Theorem B].

for PL-manifolds or smooth manifolds which is given by imposing conditions on the stable tangent bundle. Examples are unoriented bordism, oriented bordism, framed bordism. Then any bordism class can be represented by an aspherical closed manifold. If two aspherical closed manifolds represent the same bordism class, then one can find an aspherical bordism between them. See [Davis2002, Remarks 15.1] and [Davis&Januszkiewicz1991, Theorem B].

6 The Borel Conjecture

Definition 6.1 [Topologically rigid].

We call a closed manifold  topologically rigid if any homotopy equivalence

topologically rigid if any homotopy equivalence  with a closed manifold

with a closed manifold  as source is homotopic to a homeomorphism.

as source is homotopic to a homeomorphism.

The Poincare Conjecture is equivalent to the statement that any sphere  is topologically rigid.

is topologically rigid.

Conjecture 6.2 [Borel Conjecture].

Every aspherical closed manifold is topologically rigid.

In particular the Borel Conjecture 6.2 implies because of Theorem 2.1 that two aspherical closed manifolds are homeomorphic if and only if their fundamental groups are isomorphic.

Remark 6.3 [The Borel Conjecture in low dimensions].

The Borel Conjecture is true in dimension  by the classification of closed manifolds of dimension

by the classification of closed manifolds of dimension  . It is true in dimension

. It is true in dimension  if Thurston's Geometrization Conjecture is true. This follows from results of Waldhausen (see Hempel [Hempel1976, Lemma 10.1 and Corollary 13.7]) and Turaev (see [Turaev1988]) as explained for instance in [Kreck&Lück2009, Section 5]. A proof of Thurston's Geometrization Conjecture is given in [Morgan&Tian2008] following ideas of Perelman.

if Thurston's Geometrization Conjecture is true. This follows from results of Waldhausen (see Hempel [Hempel1976, Lemma 10.1 and Corollary 13.7]) and Turaev (see [Turaev1988]) as explained for instance in [Kreck&Lück2009, Section 5]. A proof of Thurston's Geometrization Conjecture is given in [Morgan&Tian2008] following ideas of Perelman.

Remark 6.4 [Topological rigidity for non-aspherical manifolds].

Topological rigidity phenomenons do hold also for some non-aspherical closed manifolds. For instance the sphere  is topologically rigid by the Poincaré Conjecture. The Poincaré Conjecture is known to be true in all dimensions. This follows in high dimensions from the

is topologically rigid by the Poincaré Conjecture. The Poincaré Conjecture is known to be true in all dimensions. This follows in high dimensions from the  -cobordism theorem, in dimension four from the work of Freedman [Freedman1982], in dimension three from the work of Perelman as explained in [Kleiner&Lott2006, Morgan&Tian2007] and and in dimension two from the classification of surfaces. Many more examples of classes of manifolds which are topologically rigid are given and analyzed in Kreck-Lück [Kreck&Lück2009]. For instance the connected sum of closed manifolds of dimension

-cobordism theorem, in dimension four from the work of Freedman [Freedman1982], in dimension three from the work of Perelman as explained in [Kleiner&Lott2006, Morgan&Tian2007] and and in dimension two from the classification of surfaces. Many more examples of classes of manifolds which are topologically rigid are given and analyzed in Kreck-Lück [Kreck&Lück2009]. For instance the connected sum of closed manifolds of dimension  which are topologically rigid and whose fundamental groups do not contain elements of order two, is again topologically rigid and the connected sum of two manifolds is in general not aspherical (see Lemma 4.2). The product

which are topologically rigid and whose fundamental groups do not contain elements of order two, is again topologically rigid and the connected sum of two manifolds is in general not aspherical (see Lemma 4.2). The product  is topologically rigid if and only if

is topologically rigid if and only if  and

and  are odd.

are odd.

Remark 6.5 [The Borel Conjecture does not hold in the smooth category].

The Borel Conjecture 6.2 is false in the smooth category, i.e., if one replaces topological manifold by smooth manifold and homeomorphism by diffeomorphism. The torus  for

for  is an example (see [Wall1999, 15A]). Other counterexample involving negatively curved manifolds are constructed by Farrell-Jones [Farrell&Jones1989, Theorem 0.1].

is an example (see [Wall1999, 15A]). Other counterexample involving negatively curved manifolds are constructed by Farrell-Jones [Farrell&Jones1989, Theorem 0.1].

Remark 6.6 [The Borel Conjecture versus Mostow rigidity].

The examples of Farrell-Jones [Farrell&Jones1989, Theorem 0.1] give actually more. Namely, it yields for given  a closed Riemannian manifold

a closed Riemannian manifold  whose sectional curvature lies in the interval

whose sectional curvature lies in the interval ![[1-\epsilon,-1 + \epsilon]](/images/math/0/0/6/00653fd41bf6fe23bfe86de24c6998bc.png) and a closed hyperbolic manifold

and a closed hyperbolic manifold  such that

such that  and

and  are homeomorphic but no diffeomorphic. The idea of the construction is essentially to take the connected sum of

are homeomorphic but no diffeomorphic. The idea of the construction is essentially to take the connected sum of  with exotic spheres. Notice that by definition

with exotic spheres. Notice that by definition  were hyperbolic if we would take

were hyperbolic if we would take  . Hence this example is remarkable in view of Mostow rigidity, which predicts for two closed hyperbolic manifolds

. Hence this example is remarkable in view of Mostow rigidity, which predicts for two closed hyperbolic manifolds  and

and  that they are isometrically diffeomorphic if and only if

that they are isometrically diffeomorphic if and only if  and any homotopy equivalence

and any homotopy equivalence  is homotopic to an isometric diffeomorphism. One may view the Borel Conjecture as the topological version of Mostow rigidity. The conclusion in the Borel Conjecture is weaker, one gets only homeomorphisms and not isometric diffeomorphisms, but the assumption is also weaker, since there are many more aspherical closed topological manifolds than hyperbolic closed manifolds.

is homotopic to an isometric diffeomorphism. One may view the Borel Conjecture as the topological version of Mostow rigidity. The conclusion in the Borel Conjecture is weaker, one gets only homeomorphisms and not isometric diffeomorphisms, but the assumption is also weaker, since there are many more aspherical closed topological manifolds than hyperbolic closed manifolds.

Remark 6.7 [The work of Farrell-Jones].

Farrell-Jones have made deep contributions to the Borel Conjecture. They have proved it in dimension  for non-positively curved closed Riemannian manifolds, for compact complete affine flat manifolds and for aspherical closed manifolds whose fundamental group is isomorphic to the fundamental group of a complete non-positively curved Riemannian manifold which is A-regular (see [Farrell&Jones1990, Farrell&Jones1991, Farrell&Jones1993, Farrell&Jones1998]).

for non-positively curved closed Riemannian manifolds, for compact complete affine flat manifolds and for aspherical closed manifolds whose fundamental group is isomorphic to the fundamental group of a complete non-positively curved Riemannian manifold which is A-regular (see [Farrell&Jones1990, Farrell&Jones1991, Farrell&Jones1993, Farrell&Jones1998]).

The following result is due to Bartels and Lück [Bartels&Lück2009].

Theorem 6.8.

Let  be the smallest class of groups satisfying:

be the smallest class of groups satisfying:

- Every hyperbolic group belongs to

;

;

- Every

-group, i.e., a group that acts properly, isometrically and cocompactly on a complete proper

-group, i.e., a group that acts properly, isometrically and cocompactly on a complete proper  -space, belongs to

-space, belongs to  ;

;

- If

and

and  belong to

belong to  , then both

, then both  and

and  belong to

belong to  ;

;

- If

is a subgroup of

is a subgroup of  and

and  , then

, then  ;

;

- Let

be a directed system of groups (with not necessarily injective structure maps) such that

be a directed system of groups (with not necessarily injective structure maps) such that  for every

for every  . Then the directed colimit

. Then the directed colimit  belongs to

belongs to  .

.

Then every aspherical closed manifold of dimension  whose fundamental group belongs to

whose fundamental group belongs to  is topologically rigid.

is topologically rigid.

Actually, Bartels and Lück [Bartels&Lück2009] prove the Farrell-Jones Conjecture about the algebraic  - and

- and  -theory of group rings which does imply the claim appearing in Theorem 6.8 by surgery theory.

-theory of group rings which does imply the claim appearing in Theorem 6.8 by surgery theory.

Remark 6.9 [Exotic aspherical closed manifolds].

Theorem 6.8 implies that the exotic aspherical manifolds mentioned in Subsection 3.7 satisfy the Borel Conjecture in dimension  since their universal coverings are

since their universal coverings are  -spaces.

-spaces.

Remark 6.10 [Directed colimits of hyperbolic groups].

There are also a variety of interesting groups such as lacunary groups in the sense of Olshanskii-Osin-Sapir [Olshankskii&Osin&Sapir2007] or groups with expanders as they appear in the counterexample to the Baum-Connes Conjecture with coefficients due to Higson-Lafforgue-Skandalis [Higson&Lafforgue&Skandalis2002] and which have been constructed by Arzhantseva-Delzant [Arzhantseva&Delzant2008, Theorem 7.11 and Theorem 7.12]. Since these arise as colimits of directed systems of hyperbolic groups, they do satisfy the Farrell-Jones Conjecture and the Borel Conjecture in dimension  by Bartels and Lück [Bartels&Lück2009]. The Bost Conjecture has also been proved for colimits of hyperbolic groups by Bartels-Echterhoff-Lück [Bartels&Echterhoff&Lück2008].

by Bartels and Lück [Bartels&Lück2009]. The Bost Conjecture has also been proved for colimits of hyperbolic groups by Bartels-Echterhoff-Lück [Bartels&Echterhoff&Lück2008].

7 Poincaré duality groups

In this section we deal with the question when a group  is the fundamental group of an aspherical closed manifold. The following definition is due to Johnson-Wall [Johnson&Wall1972].

is the fundamental group of an aspherical closed manifold. The following definition is due to Johnson-Wall [Johnson&Wall1972].

Definition 7.1 [Poincaré duality group].

A group  is called a Poincaré duality group of dimension

is called a Poincaré duality group of dimension  if the following conditions holds:

if the following conditions holds:

- The group

is of type FP, i.e., the trivial

is of type FP, i.e., the trivial  -module

-module  possesses a finite-dimensional projective

possesses a finite-dimensional projective  -resolution by finitely generated projective

-resolution by finitely generated projective  -modules;

-modules;

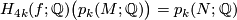

- We get an isomorphism of abelian groups

Conjecture 7.2 [Poincaríe duality groups].

A finitely presented group is a  -dimensional Poincaré duality group if and only if it is the fundamental group of an aspherical closed

-dimensional Poincaré duality group if and only if it is the fundamental group of an aspherical closed  -dimensional topological manifold.

-dimensional topological manifold.

A topological space  is called an absolute neighborhood retract or briefly

is called an absolute neighborhood retract or briefly  if for every normal space

if for every normal space  , every closed subset

, every closed subset  and every (continuous) map

and every (continuous) map  there exists an open neighborhood

there exists an open neighborhood  of

of  in

in  together with an extension

together with an extension  of

of  to

to  . A compact

. A compact  -dimensional homology

-dimensional homology  -manifold

-manifold  is a compact absolute neighborhood retract such that it has a countable basis for its topology, has finite topological dimension and for every

is a compact absolute neighborhood retract such that it has a countable basis for its topology, has finite topological dimension and for every  the abelian group

the abelian group  is trivial for

is trivial for  and infinite cyclic for

and infinite cyclic for  . A closed

. A closed  -dimensional topological manifold is an example of a compact

-dimensional topological manifold is an example of a compact  -dimensional homology

-dimensional homology  -manifold (see [Daverman1986, Corollary 1A in V.26 page 191]). For a proof of the next result we refer to [Lück2008, Section 5].

-manifold (see [Daverman1986, Corollary 1A in V.26 page 191]). For a proof of the next result we refer to [Lück2008, Section 5].

Theorem 7.3.

Suppose that the torsionfree group  belongs to the class

belongs to the class  occurring in Theorem 6.8 and its cohomological dimension is

occurring in Theorem 6.8 and its cohomological dimension is  . Then

. Then  is the fundamental group of a compact homology

is the fundamental group of a compact homology  -manifold.

-manifold.

Remark 7.4 [Compact homology  -manifolds versus closed topological manifolds].

-manifolds versus closed topological manifolds].

One would prefer if in the conclusion of Theorem 7.3 one could replace ``compact homology  -manifold by ``closed topological manifold. There are compact homology

-manifold by ``closed topological manifold. There are compact homology  -manifolds that are not homotopy equivalent to closed manifolds. But no example of an aspherical compact homology

-manifolds that are not homotopy equivalent to closed manifolds. But no example of an aspherical compact homology  -manifold that is not homotopy equivalent to a closed topological manifold is known. We refer for instance to [Bryant&Ferry&Mio&Weinberger1996, Ferry&Pedersen1995, Quinn1983, Quinn1987, Ranicki1992] for more information about this topic.

-manifold that is not homotopy equivalent to a closed topological manifold is known. We refer for instance to [Bryant&Ferry&Mio&Weinberger1996, Ferry&Pedersen1995, Quinn1983, Quinn1987, Ranicki1992] for more information about this topic.

8 Product decompositions

In this section we show that, roughly speaking, an aspherical closed manifold  is a product

is a product  if and only if its fundamental group is a product

if and only if its fundamental group is a product  and that such a decomposition is unique up to homeomorphism. A proof of the next result can be found in [Lück2008, Section 6].

and that such a decomposition is unique up to homeomorphism. A proof of the next result can be found in [Lück2008, Section 6].

Theorem 8.1 [Product decomposition].

Let be an aspherical closed manifold of dimension

be an aspherical closed manifold of dimension  with fundamental group

with fundamental group  . Suppose we have a product decomposition

. Suppose we have a product decomposition

,

,  and

and  belong to the class

belong to the class  occurring in Theorem 6.8. Assume that the cohomological dimension

occurring in Theorem 6.8. Assume that the cohomological dimension  is different from

is different from  ,

,  and

and  for

for  and

and  . Then:

. Then:

- There are aspherical closed topological manifolds

and

and  together with isomorphisms and maps

together with isomorphisms and maps for

for

such that is a homeomorphism and

such that is a homeomorphism and

(up to inner automorphisms) for

(up to inner automorphisms) for  ;

;

- Suppose we have another such choice of aspherical closed manifolds

and

and  together with isomorphisms and maps

together with isomorphisms and maps for

for

such that the map

such that the map  is a homotopy equivalence and

is a homotopy equivalence and  (up to inner automorphisms) for

(up to inner automorphisms) for  . Then there are for

. Then there are for  homeomorphisms

homeomorphisms  such that

such that  and

and  holds for

holds for  .

.

Remark 8.2 [Product decompositions and non-positive sectional curvature].

The following result has been proved by Gromoll-Wolf [Gromoll&Wolf1971, Theorem 2]. Let  be a closed Riemannian manifold with non-positive sectional curvature. Suppose that we are given a splitting of its fundamental group

be a closed Riemannian manifold with non-positive sectional curvature. Suppose that we are given a splitting of its fundamental group  and that the center of

and that the center of  is trivial. Then this splitting comes from an isometric product decomposition of closed Riemannian manifolds of non-positive sectional curvature

is trivial. Then this splitting comes from an isometric product decomposition of closed Riemannian manifolds of non-positive sectional curvature  .

.

9 The Novikov Conjecture

Let

be a group and let

be a group and let  be a map from a closed oriented smooth manifold

be a map from a closed oriented smooth manifold  to

to  . Let

. Let

-class of

-class of  . Its

. Its  -th entry

-th entry  is a certain homogeneous polynomial of degree

is a certain homogeneous polynomial of degree  in the rational Pontrjagin classes

in the rational Pontrjagin classes  for

for  such that the coefficient

such that the coefficient  of the monomial

of the monomial  is different from zero. The

is different from zero. The  -class

-class  is determined by all the rational Pontrjagin classes and vice versa. The

is determined by all the rational Pontrjagin classes and vice versa. The  -class depends on the tangent bundle and thus on the differentiable structure of

-class depends on the tangent bundle and thus on the differentiable structure of  . For

. For  define the higher signature of

define the higher signature of  associated to

associated to  and

and  to be the integer

to be the integer ![\displaystyle \begin{array}{rcl} \operatorname{sign}_x(M,u) & := & \langle \mathcal{L}(M) \cup f^* x,[M] \rangle. \end{array}](/images/math/e/5/f/e5f24580532eca318a58b99c3a8bc71d.png)

for

for  is homotopy invariant if for two closed oriented smooth manifolds

is homotopy invariant if for two closed oriented smooth manifolds  and

and  with reference maps

with reference maps  and

and  we have

we have

such that

such that  and

and  are homotopic. If

are homotopic. If  , then the higher signature

, then the higher signature  is by the Hirzebruch signature formula (see [Hirzebruch1958, Hirzebruch1971]) the signature of

is by the Hirzebruch signature formula (see [Hirzebruch1958, Hirzebruch1971]) the signature of  itself and hence an invariant of the oriented homotopy type. This is one motivation for the following conjecture.

itself and hence an invariant of the oriented homotopy type. This is one motivation for the following conjecture.

Conjecture 9.1 [Novikov Conjecture].

Let  be a group. Then

be a group. Then  is homotopy invariant for all

is homotopy invariant for all  .

.

This conjecture appears for the first time in the paper by Novikov [Novikov1970, §11]. A survey about its history can be found in [Ferry&Ranicki&Rosenberg1995b]. More information can be found for instance in [Ferry&Ranicki&Rosenberg1995, Ferry&Ranicki&Rosenberg1995a, Kreck&Lück2005].

Remark 9.2 [The Novikov Conjecture and aspherical closed manifolds].

Let  be a homotopy equivalence of aspherical closed oriented manifolds. Then the Novikov Conjecture 9.1

implies that

be a homotopy equivalence of aspherical closed oriented manifolds. Then the Novikov Conjecture 9.1

implies that  . This is certainly true if

. This is certainly true if  is a diffeomorphism. On the other hand, in general the rational Pontrjagin classes are not homotopy invariants and the integral Pontrjagin classes

is a diffeomorphism. On the other hand, in general the rational Pontrjagin classes are not homotopy invariants and the integral Pontrjagin classes  are not homeomorphism invariants (see for instance [Kreck&Lück2005, Example 1.6 and Theorem 4.8]). This seems to shed doubts about the Novikov Conjecture. However, if the Borel Conjecture is true, the map

are not homeomorphism invariants (see for instance [Kreck&Lück2005, Example 1.6 and Theorem 4.8]). This seems to shed doubts about the Novikov Conjecture. However, if the Borel Conjecture is true, the map  is homotopic to a homeomorphism and the conclusion

is homotopic to a homeomorphism and the conclusion  does follow from the following deep result due to Novikov [Novikov1965a, Novikov1965, Novikov1966].

does follow from the following deep result due to Novikov [Novikov1965a, Novikov1965, Novikov1966].

Theorem 9.3 [Topological invariance of rational Pontrjagin classes].

The rational Pontrjagin classes are topological invariants, i.e. for a homeomorphism

are topological invariants, i.e. for a homeomorphism  of closed smooth manifolds we have

of closed smooth manifolds we have

and in particular

and in particular  .

.

10 Boundaries of hyperbolic groups

We mention the following result of Bartels-Lück-Weinberger [Bartels&Lück&Weinberger2009]. For the notion of the boundary of a hyperbolic group and its main properties we refer for instance to [Kapovich&Benakli2002].

Theorem 10.1.

Let  be a torsion-free hyperbolic group and let

be a torsion-free hyperbolic group and let  be an integer

be an integer  . Then the following statements are equivalent:

. Then the following statements are equivalent:

- The boundary

is homeomorphic to

is homeomorphic to  ;

;

- There is an aspherical closed topological manifold

such that

such that  , its universal covering

, its universal covering  is homeomorphic to

is homeomorphic to  and the compactification of

and the compactification of  by

by  is homeomorphic to

is homeomorphic to  ;

;

- The aspherical closed topological manifold

appearing in the assertion above is unique up to homeomorphism.

appearing in the assertion above is unique up to homeomorphism.

In general the boundary of a hyperbolic group is not locally a Euclidean space but has a fractal behavior. If the boundary  of an infinite hyperbolic group

of an infinite hyperbolic group  contains an open subset homeomorphic to Euclidean

contains an open subset homeomorphic to Euclidean  -space, then it is homeomorphic to

-space, then it is homeomorphic to  . This is proved in [Kapovich&Benakli2002, Theorem 4.4], where more information about the boundaries of hyperbolic groups can be found. For every

. This is proved in [Kapovich&Benakli2002, Theorem 4.4], where more information about the boundaries of hyperbolic groups can be found. For every  there exists a strictly negatively curved polyhedron of dimension

there exists a strictly negatively curved polyhedron of dimension  whose fundamental group

whose fundamental group  is hyperbolic, which is homeomorphic to an aspherical closed smooth manifold and whose universal covering is homeomorphic to

is hyperbolic, which is homeomorphic to an aspherical closed smooth manifold and whose universal covering is homeomorphic to  , but the boundary

, but the boundary  is not homeomorphic to

is not homeomorphic to  , see [Davis&Januszkiewicz1991, Theorem 5c.1 on page 384 and Remark on page 386]. Thus the condition that

, see [Davis&Januszkiewicz1991, Theorem 5c.1 on page 384 and Remark on page 386]. Thus the condition that  is a sphere for a torsion-free hyperbolic group is (in high dimensions) not equivalent to the existence of an aspherical closed manifold whose fundamental group is

is a sphere for a torsion-free hyperbolic group is (in high dimensions) not equivalent to the existence of an aspherical closed manifold whose fundamental group is  .

.

Remark 10.2 [The Cannon Conjecture].

We do not get information in dimensions  for the usual problems about surgery. In the case

for the usual problems about surgery. In the case  there is the conjecture of Cannon [Cannon1991] that a group

there is the conjecture of Cannon [Cannon1991] that a group  acts properly, isometrically and cocompactly on the

acts properly, isometrically and cocompactly on the  -dimensional hyperbolic plane

-dimensional hyperbolic plane  if and only if it is a hyperbolic group whose boundary is homeomorphic to

if and only if it is a hyperbolic group whose boundary is homeomorphic to  . Provided that the infinite hyperbolic group

. Provided that the infinite hyperbolic group  occurs as the fundamental group of a closed irreducible

occurs as the fundamental group of a closed irreducible  -manifold, Bestvina-Mess [Bestvina&Mess1991, Theorem 4.1] have shown that its universal covering is homeomorphic to

-manifold, Bestvina-Mess [Bestvina&Mess1991, Theorem 4.1] have shown that its universal covering is homeomorphic to  and its compactification by

and its compactification by  is homeomorphic to

is homeomorphic to  , and the Geometrization Conjecture of Thurston implies that

, and the Geometrization Conjecture of Thurston implies that  is hyperbolic and

is hyperbolic and  satisfies Cannon's conjecture. The problem is solved in the case

satisfies Cannon's conjecture. The problem is solved in the case  , namely, for a hyperbolic group

, namely, for a hyperbolic group  its boundary

its boundary  is homeomorphic to

is homeomorphic to  if and only if

if and only if  is a Fuchsian group (see [Casson&Jungreis1994, Freden1995, Gabai1991]).

is a Fuchsian group (see [Casson&Jungreis1994, Freden1995, Gabai1991]).

11 L2-invariants

Next we mention some prominent conjectures about aspherical closed manifolds and  -invariants of their universal coverings. For more information about these conjectures and their status we refer to [Lück2002] and [Lück2003].

-invariants of their universal coverings. For more information about these conjectures and their status we refer to [Lück2002] and [Lück2003].

11.1 The Hopf and the Singer Conjectures

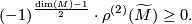

Conjecture 11.1 [Hopf Conjecture].

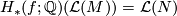

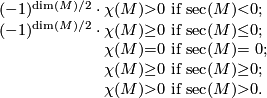

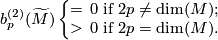

If is an aspherical closed manifold of even dimension, then

is an aspherical closed manifold of even dimension, then

is a closed Riemannian manifold of even dimension with sectional curvature

is a closed Riemannian manifold of even dimension with sectional curvature  , then

, then

Conjecture 11.2 [Singer Conjecture].

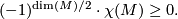

If is an aspherical closed manifold, then

is an aspherical closed manifold, then

is a closed connected Riemannian manifold with negative sectional curvature, then

is a closed connected Riemannian manifold with negative sectional curvature, then

11.2 L2--torsion and aspherical closed manifolds

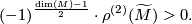

Conjecture 11.3 [ -torsion for aspherical closed manifolds].

-torsion for aspherical closed manifolds].

is an aspherical closed manifold of odd dimension, then

is an aspherical closed manifold of odd dimension, then  is

is  -

- -acyclic and

-acyclic and

is a closed connected Riemannian manifold of odd dimension with negative sectional curvature, then

is a closed connected Riemannian manifold of odd dimension with negative sectional curvature, then  is

is  -

- -acyclic and

-acyclic and

is an aspherical closed manifold whose fundamental group contains an amenable infinite normal subgroup, then

is an aspherical closed manifold whose fundamental group contains an amenable infinite normal subgroup, then  is

is  -

- -acyclic and

-acyclic and

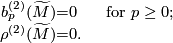

11.3 Simplicial volume and L2-invariants

Conjecture 11.4 [Simplicial volume and  -invariants].

-invariants].

be an aspherical closed orientable manifold. Suppose that its simplicial volume

be an aspherical closed orientable manifold. Suppose that its simplicial volume  vanishes. Then

vanishes. Then  is of determinant class and

is of determinant class and

11.4 The Zero-in-the-Spectrum Conjecture

Conjecture 11.5 [Zero-in-the-spectrum Conjecture].

Let be a complete Riemannian manifold. Suppose that

be a complete Riemannian manifold. Suppose that  is the universal covering of an aspherical closed Riemannian manifold

is the universal covering of an aspherical closed Riemannian manifold  (with the Riemannian metric coming from

(with the Riemannian metric coming from  ). Then for some

). Then for some  zero is in the Spectrum of the minimal closure

zero is in the Spectrum of the minimal closure

-forms on

-forms on  .

.

Remark 11.6 [Non-aspherical counterexamples to the Zero-in-the-Spectrum Conjecture].

For all of the conjectures about aspherical spaces stated in this article it is obvious that they cannot be true if one drops the condition aspherical except for the zero-in-the-Spectrum Conjecture 11.5. Farber and Weinberger [Farber&Weinberger2001] gave the first example of a closed Riemannian manifold for which zero is not in the spectrum of the minimal closure  of the Laplacian acting on smooth

of the Laplacian acting on smooth  -forms on

-forms on  for each

for each  . The construction by Higson, Roe and Schick [Higson&Roe&Schick2001] yields a plenty of such counterexamples. But there are no aspherical counterexamples known.

. The construction by Higson, Roe and Schick [Higson&Roe&Schick2001] yields a plenty of such counterexamples. But there are no aspherical counterexamples known.

12 References

- [Arzhantseva&Delzant2008] G. Arzhantseva and T. Delzant, Examples of random groups, preprint (2008).

- [Bartels&Echterhoff&Lück2008] A. Bartels, S. Echterhoff and W. Lück, Inheritance of Isomorphism Conjectures under colimits, K-theory and noncommutative geometry, EMS Ser. Congr. Rep., Eur. Math. Soc., Zürich, (2008) 41–70. MR2513332 Zbl 1159.19005

- [Bartels&Lück&Reich2008] A. Bartels, W. Lück and H. Reich, On the Farrell-Jones Conjecture and its applications, Journal of Topology 1 (2008), 57–86. MR2365652 (2008m:19001) Zbl 1141.19002

- [Bartels&Lück&Weinberger2009] Template:Bartels&Lück&Weinberger2009

- [Bartels&Lück2009] A. Bartels and W. Lück, The Borel Conjecture for hyperbolic and CAT(0)-groups,(2009). Available at the arXiv:0901.0442

- [Belegradek2006] I. Belegradek, Aspherical manifolds, relative hyperbolicity, simplicial volume and assembly maps, Algebr. Geom. Topol. 6 (2006), 1341–1354 (electronic). MR2253450 (2007f:57004) Zbl 1137.20035

- [Bestvina&Mess1991] M. Bestvina and G. Mess, The boundary of negatively curved groups, J. Amer. Math. Soc. 4 (1991), no.3, 469–481. MR1096169 (93j:20076) Zbl 0767.20014

- [Bryant&Ferry&Mio&Weinberger1996] J. Bryant, S. Ferry, W. Mio and S. Weinberger, Topology of homology manifolds, Ann. of Math. (2) 143 (1996), no.3, 435–467. MR1394965 (97b:57017) Zbl 0867.57016

- [Cannon1991] J. W. Cannon, The theory of negatively curved spaces and groups, Ergodic theory, symbolic dynamics, and hyperbolic spaces (Trieste, 1989), Oxford Univ. Press (1991), 315–369. MR1130181 () Zbl 0764.57002

- [Casson&Jungreis1994] A. Casson and D. Jungreis, Convergence groups and Seifert fibered

-manifolds, Invent. Math. 118 (1994), no.3, 441–456. MR1296353 (96f:57011) Zbl 0840.57005

-manifolds, Invent. Math. 118 (1994), no.3, 441–456. MR1296353 (96f:57011) Zbl 0840.57005

- [Charney&Davis1995] R. M. Charney and M. W. Davis, Strict hyperbolization, Topology 34 (1995), no.2, 329–350. MR1318879 (95m:57034) Zbl 0826.53040

- [Daverman1986] R. J. Daverman, Decompositions of manifolds, Academic Press Inc., 1986. MR872468 (88a:57001) Zbl 1130.57001

- [Davis&Januszkiewicz1991] M. W. Davis and T. Januszkiewicz, Hyperbolization of polyhedra, J. Differential Geom. 34 (1991), no.2, 347–388. MR1906785 (2003e:57038) Zbl 1028.57020

- [Davis1983] M. W. Davis, Groups generated by reflections and aspherical manifolds not covered by Euclidean space, Ann. of Math. (2) 117 (1983), no.2, 293–324. MR690848 (86d:57025) Zbl 0531.57041

- [Davis2002] M. Davis, Exotic aspherical manifolds, Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics, Trieste, 2002. MR1937019 (2004a:57031) Zbl 1070.57012

- [Davis2008] M. W. Davis, The geometry and topology of Coxeter groups, London Mathematical Society Monographs Series, 32. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2008. MR2360474 (2008k:20091) Zbl 1142.20020

- [Farber&Weinberger2001] M. Farber and S. Weinberger, On the zero-in-the-spectrum conjecture, Ann. of Math. (2) 154 (2001), no.1, 139–154. MR1847591 (2003b:58044) Zbl 0992.58012

- [Farrell&Jones1989] F. T. Farrell and L. E. Jones, Negatively curved manifolds with exotic smooth structures, J. Amer. Math. Soc. 2 (1989), no.4, 899–908. MR1002632 (90f:53075) Zbl 0698.53027

- [Farrell&Jones1990] F. T. Farrell and L. E. Jones, Classical aspherical manifolds, Published for the Conference Board of the Mathematical Sciences, Washington, DC, 1990. MR1056079 (91k:57001) Zbl 0729.57001

- [Farrell&Jones1991] F. T. Farrell and L. E. Jones, Rigidity in geometry and topology, Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians, Vol. I, II (Kyoto, 1990), 653–663, Math. Soc. Japan, Tokyo, 1991. MR1159252 (93g:57041) Zbl 0745.57008

- [Farrell&Jones1993] F. T. Farrell and L. E. Jones, Topological rigidity for compact non-positively curved manifolds, Differential geometry: Riemannian geometry (Los Angeles, CA, 1990), Proc. Sympos. Pure Math., 54, Part 3, Amer. Math. Soc., Providence, RI, (1993), 229–274. MR1216623 (94m:57067) Zbl 0796.53043

- [Farrell&Jones1998] F. T. Farrell and L. E. Jones, Rigidity for aspherical manifolds with

, Asian J. Math. 2 (1998), no.2, 215–262. MR1639544 (99j:57032)Zbl 0912.57012

, Asian J. Math. 2 (1998), no.2, 215–262. MR1639544 (99j:57032)Zbl 0912.57012

- [Ferry&Pedersen1995] S. C. Ferry and E. K. Pedersen, Epsilon surgery theory, Novikov conjectures, index theorems and rigidity, Vol. 2 (Oberwolfach, 1993), Cambridge Univ. Press (1995), 167–226. MR1388311 (97g:57044) Zbl 0956.57020

- [Ferry&Ranicki&Rosenberg1995] S. C. Ferry, A. A. Ranicki and J. Rosenberg, Novikov conjectures, index theorems and rigidity. Vol. 1. London Math. Soc. Lecture Note Ser., 226, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1995. MR1388294 (96m:57002) Zbl 0829.00027

- [Ferry&Ranicki&Rosenberg1995a] S. C. Ferry, A. A. Ranicki and J. Rosenberg, Novikov conjectures, index theorems and rigidity. Vol. 2, London Math. Soc. Lecture Note Ser., 227, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1995. MR1388306 (96m:57003) Zbl 0829.00028

- [Ferry&Ranicki&Rosenberg1995b] S. C. Ferry, A. A. Ranicki and J. Rosenburg, A history and survey of the Novikov conjecture in Ferry&Ranicki&Rosenberg1995 7–66, London Math. Soc. Lecture Note Ser., 226, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1995. MR1388295 (97f:57036) Zbl 0954.57018

- [Freden1995] E. M. Freden, Negatively curved groups have the convergence property. I, Ann. Acad. Sci. Fenn. Ser. A I Math. 20 (1995), no.2, 333–348. MR1346817 (96g:20054) Zbl 0847.20031

- [Freedman1982] M. H. Freedman, The topology of four-dimensional manifolds, J. Differential Geom. 17 (1982), no.3, 357–453. MR679066 (84b:57006) Zbl 0528.57011

- [Gabai1991] D. Gabai, Convergence groups are Fuchsian groups, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) 25 (1991), no.2, 395-402. MR1189862 (93m:20065) Zbl 0785.57004

- [Gallot&Hulin&Lafontaine1987] S. Gallot, D. Hulin and J. Lafontaine, Riemannian geometry, Springer-Verlag, 1987. MR2088027 (2005e:53001) Zbl 1068.53001

- [Gromoll&Wolf1971] D. Gromoll and J. A. Wolf, Some relations between the metric structure and the algebraic structure of the fundamental group in manifolds of nonpositive curvature, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 77 (1971), 545–552. MR0281122 (43 #6841) Zbl 0237.53037

- [Gromov1987] M. Gromov, Hyperbolic groups, Essays in group theory,Math. Sci. Res. Inst. Publ., 8, Springer, New York, (1987) 75–263. MR0919829 (89e:20070) Zbl 0634.20015

- [Helgason2001] S. Helgason, Differential geometry, Lie groups, and symmetric spaces, Corrected reprint of the 1978 original. Graduate Studies in Mathematics, 34. American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI, 2001. MR1834454 (2002b:53081) Zbl 0993.53002

- [Hempel1976] J. Hempel,

-Manifolds, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N. J., 1976. MR0415619 (54 #3702) Zbl 1058.57001

-Manifolds, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N. J., 1976. MR0415619 (54 #3702) Zbl 1058.57001

- [Higson&Lafforgue&Skandalis2002] N. Higson, V. Lafforgue and G. Skandalis, Counterexamples to the Baum-Connes conjecture, Geom. Funct. Anal. 12 (2002), no.2, 330–354. MR1911663 (2003g:19007) Zbl 1014.46043

- [Higson&Roe&Schick2001] N. Higson, J. Roe and T. Schick, Spaces with vanishing

-homology and their fundamental groups (after Farber and Weinberger), Geom. Dedicata 87 (2001), no.1-3, 335–343. MR1866855 (2002m:57031) Zbl 991.57002

-homology and their fundamental groups (after Farber and Weinberger), Geom. Dedicata 87 (2001), no.1-3, 335–343. MR1866855 (2002m:57031) Zbl 991.57002

- [Hirzebruch1958] F. Hirzebruch, Automorphe Formen und der Satz von Riemann-Roch 1958 Symposium internacional de topología algebraica International symposium on algebraic topology, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and UNESCO, Mexico City,(1958) 129–144 MR0103280 (21 #2058) Zbl 0129.29801

- [Hirzebruch1971] F. Hirzebruch, The signature theorem: reminiscences and recreation, Prospects in mathematics (Proc. Sympos., Princeton Univ., Princeton, N.J., 1970), Ann. of Math. Studies, No. 70, Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, N.J. (1971) 3–31. MR0368023 (51 #4265) Zbl 0252.58009

- [Johnson&Wall1972] F. E. A. Johnson and C. T. C. Wall, On groups satisfying Poincaré duality, Ann. of Math. (2) 96 (1972), 592–598. MR0311796 (47 #358) Zbl 0245.57005

- [Kapovich&Benakli2002] I. Kapovich and N. Benakli, Boundaries of hyperbolic groups, in Combinatorial and geometric group theory (New York, 2000/Hoboken, NJ, 2001), Contemp. Math., 296, Amer. Math. Soc., Providence, RI, (2002) 39–93. MR1921706 (2004e:20075) Zbl 1044.20028

- [Kleiner&Lott2006] Template:Kleiner&Lott2006

- [Kreck&Lück2005] M. Kreck and W. Lück, The Novikov conjecture, Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, 2005. MR2117411 (2005i:19003) Zbl 1058.19001

- [Kreck&Lück2009] M. Kreck and W. Lück, Topological rigidity for non-aspherical manifolds, Pure Appl. Math. Q. 5 (2009), no.3, Special Issue: In honor of Friedrich Hirzebruch., 873–914. MR2532709 (2010g:57026) Zbl 1196.57018

- [Leeb1995] B. Leeb,

-manifolds with(out) metrics of nonpositive curvature, Invent. Math. 122 (1995), no.2, 277–289. MR1358977 (97g:57015) Zbl 0840.53031

-manifolds with(out) metrics of nonpositive curvature, Invent. Math. 122 (1995), no.2, 277–289. MR1358977 (97g:57015) Zbl 0840.53031

- [Lück&Reich2005] W. Lück and H. Reich, The Baum-Connes and the Farrell-Jones conjectures in

- and

- and  -theory, Handbook of K-theory. Vol. 1, 2, 703–842, Springer, Berlin, 2005. MR2181833 (2006k:19012) Zbl 1120.19001

-theory, Handbook of K-theory. Vol. 1, 2, 703–842, Springer, Berlin, 2005. MR2181833 (2006k:19012) Zbl 1120.19001

- [Lück2002] W. Lück,

-invariants: theory and applications to geometry and

-invariants: theory and applications to geometry and  -theory, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2002. MR1926649 (2003m:58033) Zbl 1009.55001

-theory, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2002. MR1926649 (2003m:58033) Zbl 1009.55001

- [Lück2003] Template:Lück2003

- [Lück2008] W. Lück, Survey on aspherical manifolds, to appear in the proceedings of the 5-th ECM in Amsterdam (2008).

- [Mess1990] G. Mess, Examples of Poincaré duality groups, Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 110 (1990), no.4, 1145–1146. MR1019274 (91c:20075) Zbl 0709.57025

- [Morgan&Tian2007] J. Morgan and G. Tian, Ricci flow and the Poincaré conjecture, Clay Mathematics Monographs, 3. American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI; Clay Mathematics Institute, Cambridge, MA, 2007 MR2334563 (2008d:57020) Zbl 1179.57045

- [Morgan&Tian2008] J. Morgan and G. Tian, Completion of the Proof of the Geometrization Conjecture, (2008). Available at the arXiv:0809.4040.

- [Novikov1965] S. P. Novikov, Rational Pontrjagin classes. Homeomorphism and homotopy type of closed manifolds. I, Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR Ser. Mat. 29 (1965), 1373–1388. MR0196764 (33 #4950) Zbl 0146.19601

- [Novikov1965a] S. P. Novikov, Topological invariance of rational classes of Pontrjagin, Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 163 (1965), 298–300. MR0193644 (33 #1860) Zbl 0146.19502

- [Novikov1966] S. P. Novikov, On manifolds with free abelian fundamental group and their application, Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR Ser. Mat. 30 (1966), 207–246.

- [Novikov1970] S. P. Novikov, Algebraic construction and properties of Hermitian analogs of

-theory over rings with involution from the viewpoint of Hamiltonian formalism. Applications to differential topology and the theory of characteristic classes. I. II, Math. USSR-Izv. 4 (1970), 257–292; ibid. 4 (1970), 479–505; translated from Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR Ser. Mat. 34 (1970), 253–288; ibid. 34 (1970), 475. MR0292913 (45 #1994) Zbl 0216.45003 Zbl 0233.57009

-theory over rings with involution from the viewpoint of Hamiltonian formalism. Applications to differential topology and the theory of characteristic classes. I. II, Math. USSR-Izv. 4 (1970), 257–292; ibid. 4 (1970), 479–505; translated from Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR Ser. Mat. 34 (1970), 253–288; ibid. 34 (1970), 475. MR0292913 (45 #1994) Zbl 0216.45003 Zbl 0233.57009

- [Olshankskii&Osin&Sapir2007] Template:Olshankskii&Osin&Sapir2007

- [Quinn1983] F. Quinn, Resolutions of homology manifolds, and the topological characterization of manifolds, Invent. Math. 72 (1983), no.2, 267–284. MR700771 (85b:57023) Zbl 0603.57008

- [Quinn1987] F. Quinn, An obstruction to the resolution of homology manifolds, Michigan Math. J. 34 (1987), no.2, 285–291. MR894878 (88j:57016) Zbl 0652.57011

- [Ranicki1992] A. A. Ranicki, Algebraic

-theory and topological manifolds, Cambridge University Press, 1992. MR1211640 (94i:57051) Zbl 0767.57002

-theory and topological manifolds, Cambridge University Press, 1992. MR1211640 (94i:57051) Zbl 0767.57002

- [Scott1983] P. Scott, The geometries of

-manifolds, Bull. London Math. Soc. 15 (1983), no.5, 401–487. MR705527 (84m:57009) Zbl 0662.57001

-manifolds, Bull. London Math. Soc. 15 (1983), no.5, 401–487. MR705527 (84m:57009) Zbl 0662.57001

- [Turaev1988] V. G. Turaev, Homeomorphisms of geometric three-dimensional manifolds, (Russian). Mat. Zametki 43 (1988), no.4, 533–542, 575; translation in Math. Notes 43 (1988), no. 3-4, 307–312. MR940851 (89f:57015) Zbl 0646.57008

- [Wall1999] C. T. C. Wall, Surgery on compact manifolds, American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI, 1999. MR1687388 (2000a:57089) Zbl 0935.57003

- [Whitehead1978] G. W. Whitehead, Elements of homotopy theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 61. Springer-Verlag, New York-Berlin, 1978. MR516508 (80b:55001) Zbl 0406.55001

13 External links

The Wikipedia page on aspherical spaces.